Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

As part of General U. S. Grant’s Overland Campaign in 1864, the Union army was advancing in a southwest direction toward Robert E. Lee’s army and the Confederate capitol at Richmond. Both armies had suffered heavy casualties in the campaign, and Lee’s men were also dealing with a shortage of supplies brought on by the Union’s disruption of the Virginia Central Railroad.

The two forces were destined to meet on May 31, 1864, at a small crossroads in Virginia known as Cold Harbor. The ensuing battle would become a bloodbath. Lee’s Confederate Army would take an estimated 4,595 casualties, with 83 of those killed. But the Union army would fare far worse, seeing an astounding 12,737 casualties, with 1,844 killed, 9,077 wounded, and 1,816 missing or captured when Grant sent wave after wave against Lee’s firmly entrenched forces.

For 12 days the main army of Grant’s Army of the Potomac and Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia squared off in a series of attacks, artillery duels, and cavalry actions. Finally, on June 12, Grant’s corps commanders convinced him to end the assault. His devastating losses would lead to accusations that Grant was a butcher, and he himself would later write, “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. … No advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.”

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

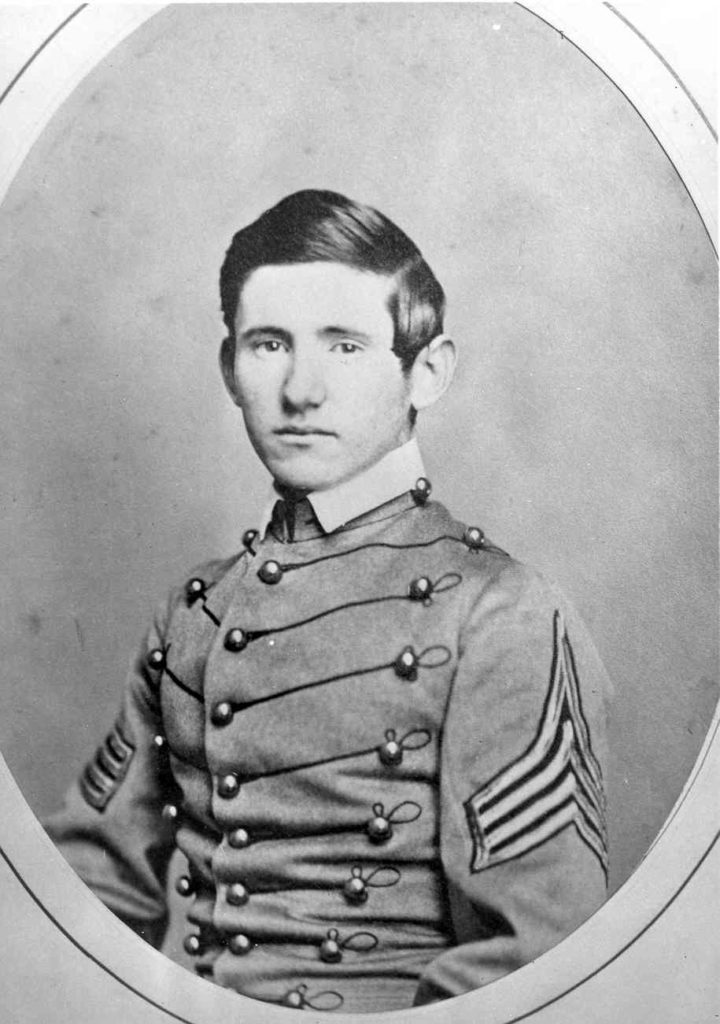

Heavy skirmishing marked the early stages of the fighting in the oppressive heat that enveloped Cold Harbor. Late in the day on May 31, 1864, the call went out from General George Meade’s headquarters that a volunteer would be needed to carry orders through enemy lines to General Phil Sheridan, commanding the Union cavalry. First Lieutenant George Lewis Gillespie, Jr., a 22-year old Tennessean who had finished second in his class at West Point, answered that call. Gillespie had seen many of his Southern classmates leave before graduating to fight for the Confederacy. Although from a border state, Gillespie had chosen to remain loyal to the Union and had been assigned to the Army Corps of Engineers when he received his commission.

Gillespie had received his baptism of fire at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862. There, he had been helping build pontoon bridges in preparation for the battle when he and his fellow engineers came under heavy fire. He would also be part of the Union fighting force at Gettysburg, where he was charged with defending Major General George Meade’s base of operations.

Few details are available outlining Gillespie’s journey through the lines, although it is known that he quickly came under heavy fire when he was spotted by skirmishing rebels. He was captured and faced spending the rest of the war in Libby Prison, but somehow escaped. Continuing his mission, the young lieutenant slowly worked his way through the enemy entrenchments until he was spotted once again. Ordered to surrender a second time, Gillespie chose to run. With Confederate bullets whizzing past his ear, he dashed through the swampy terrain until he had evaded his pursuers. He continued on his mission and successfully delivered Meade’s orders to Sheridan.

By war’s end Gillespie had attained the rank of brevet lieutenant-colonel. Choosing to remain in the Army, he constructed lighthouses, fortifications, and harbors as part of the Corps of Engineers. He would rise to the rank of major general, served as acting U.S. Secretary of War in 1901, had charge of the ceremonies at President William McKinley’s funeral that same year, and supervised the laying of the cornerstone of the Army War College building in 1903. However, the highlight of his military career came on October 27, 1897, some 33 years after his harrowing encounters with the enemy at Cold Harbor, when Gillespie was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on May 31, 1864.

In the years between Gillespie’s actions and the awarding of his Medal of Honor, numerous patriotic and political organizations were founded. Many of those organizations created member badges, or badges to commemorate veterans’ reunions, and a large number of those badges looked remarkably similar to the Medal of Honor. The badge of the Grand Army of the Republic, one of the largest and most influential of these organizations, produced a badge that was nearly indistinguishable from the Medal of Honor. Understandably, those who had been awarded the Medal of Honor took umbrage, and pressure was brought to bear on the U.S. Congress to give exclusivity to the Medal of Honor’s design. Gillespie was one of the leaders in applying that pressure.

When Congress finally agreed, Secretary of War Elihu Root asked Gillespie to lead the committee responsible for a redesign of the Medal of Honor, along with fellow Medal of Honor recipient General Horace Porter. On March 9, 1904, he submitted his patent application for his design. Eight months later, Gillespie was issued U.S. Design Patent No. 37,326. Later, he signed the patent rights over to then Secretary of War William Howard Taft. His design would become known as the “Gillespie Medal.”

General Gillespie died September 27, 1913 in Saratoga, New York. He is buried in the U.S. Military Academy Cemetery at West Point, New York.