Iwo Jima Commemoration: Sergeant Darrell Cole, the Fighting Field Music

During World War II, when U.S. Marines landed on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, they found the Japanese forced well-entrenched. It took the Marines 36 days to take the…

Sometime during the night of November 26, 1921, three years after his actions that earned him the Medal of Honor, Charles W. Whittlesey jumped into the sea between the U.S. and Cuba. It is believed that the demons that followed him after the war caught up with him.

By: Kris Cotariu Harper, EdD

When the regimental commander ordered him into the fateful attack, Charles Whittlesey, commander of the Lost Battalion responded, “All right, I’ll attack, but whether you’ll hear from me again, I don’t know.”

Charles Whittlesey, the eldest of four children, was born in Florence, Wisconsin, into a middle class family in January 1884. While he was still young, the family moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he grew up and attended school. He graduated at the top of his class from Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he was active in student leadership, an editor of the yearbook, and a contributor to two campus newspapers. He was a member of Delta Psi fraternity and was elected to the Gargoyle Society, an historic student organization whose purpose it is to promote “moral, intellectual, physical, and social growth” of the students and “improving the character of the school and its student body” (Williams College). He was popular with his peers who affectionately nicknamed “Count” and “Chick” and, even as a student, demonstrated the leadership characteristics that would serve him and his men in combat.

A Harvard Law School classmate of Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., Whittlesey graduated in 1908 and joined a New York City law firm. Three years later, however, he left the firm and went into private practice with his friend and classmate from Williams College, J. Bayard Pruyn. He later joined Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., at the Plattsburg Training Camp, a military camp in New York founded by General Leonard Wood and endorsed by former president Theodore Roosevelt, to prepare young men for the eventually of war. He completed his training in August 1916 and one year later was called to active duty and joined the American Expeditionary Force in Europe for World War I.

As a captain, Charles Whittlesey served with headquarters of the 308th Infantry Regiment, 77th Division in France. He was promoted to major in time to participate in the Meusse-Argonne, the largest, bloodiest American offensive of the war and is most famous for his role as commander of the so-called “Lost Battalion.” The name, however, is a misnomer, as it was neither a battalion nor was it lost.

The Lost Battalion consisted of two under-strength battalions in addition to two attached companies from the 307th Infantry. Captain George McMurtry, a veteran of the Spanish American War who rode with Teddy Roosevelt and the Rough Riders, was in command of the 2nd Battalion. Whittlesey was commander of the of the 1st Battalion of the 308th, but as the senior officer present, Whittlesey took command of the trapped units.

When given their orders for an offensive in the Argonne Forest in France, Whittlesey and McMurtry both claimed it was an impossible task for the two under-strength battalions. The dense forest had been held in German hands for nearly four years. It was known to be heavily fortified by German Forces with two lines of trenches, artillery, natural and man-made fortifications, and other strategic defenses.

The American regimental commander, however, ordered them to proceed regardless and Whittlesey replied, “All right, I’ll attack, but whether you’ll hear from me again, I don’t know” (Durr, 2018). The 1st and 2nd Battalions reached their objective through thick fighting but French and American units on both their flanks were stopped, allowing the Germans to surround Whittlesey and McMurtry’s units.

With inadequate means of communication – couriers, cables that could not run through the thick forest, and carrier pigeons – they were unable to communicate their position and were therefore presumed lost. In actuality, the unit was exactly where it was supposed to be. Eventually, located by air, they were misidentified as enemy forces and were fired upon by American artillery. Using the last of his eight carrier pigeons, Cher Ami (French for Dear Friend), Whittlesey sent the message, “We are along the road parallel 276.4. Our artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake stop it” (Durr, 2018).

One of the couriers, captured by the Germans, was returned with a demand for surrender which Whittlesey rejected. The American press claimed Whittlesey had responded with the message, “Go to Hell!”. Whittlesey later denied this was true. Surrender must have been tempting – supplies of food and ammunition were low; he remained surrounded and no relief was in sight. American headquarters tried to relieve the burden by carrying out what is believed to be the United States’ first aerial re-supply mission. Food, supplies and ammunition were airdropped, but landed outside the perimeter and mostly fell into German hands.

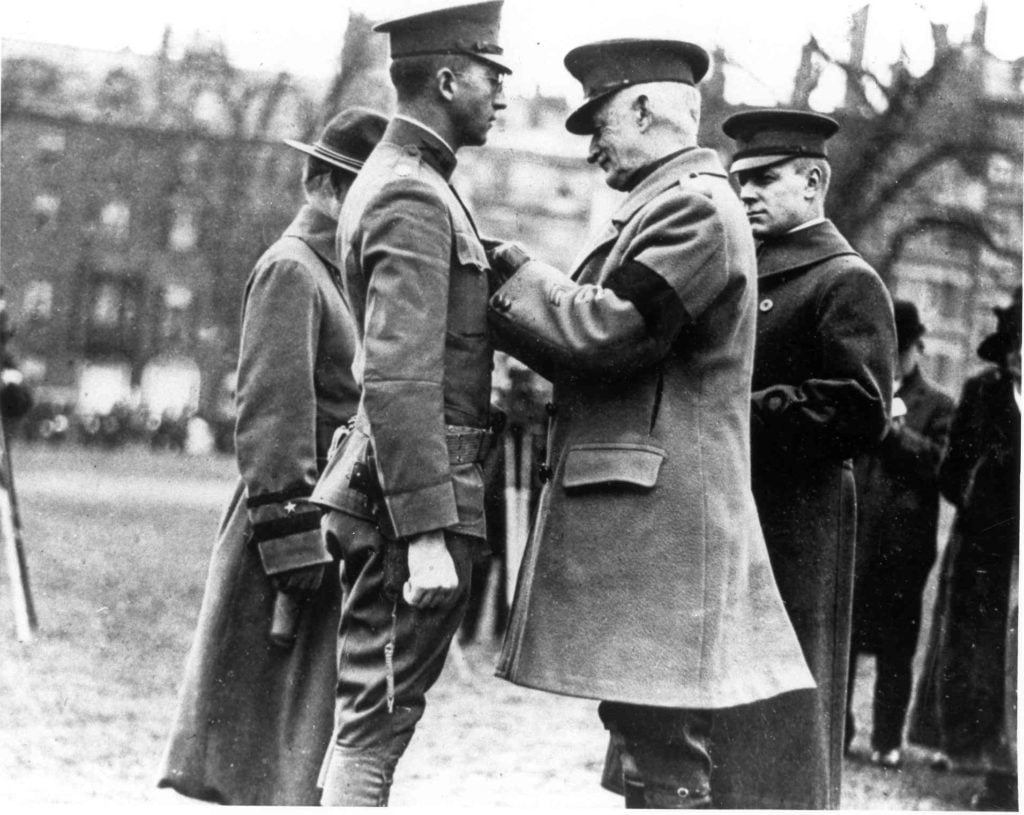

After five days, the Germans were forced to fall back, and on the sixth day, approximately 190 men were able to walk out of the site. Casualties for the Lost Battalion numbered over 350 – killed, wounded and missing. For his leadership during the five days, now-Lt. Colonel Charles Whittlesey was awarded the Medal of Honor on December 24, 1918.

After the war, Charles Whittlesey returned to his law practice and, later, found work with the Red Cross, as he tried to resume his old life. The difficulties he experienced in his transition back to civilian life were exacerbated by his notoriety as commander of the Lost Battalion and his hero status. Despite being vindicated by the military, he was criticized in the press for his decision to not surrender. The criticism and blame added to the difficulties he had in re-adjusting.

Public events and interview requests prevented him from moving forward and he was constantly reminded of his war experiences. He participated in filming a recreation of the Argonne forest battle, resulting in a 1919 silent film, The Lost Battalion, endorsed by the U.S. Government. In 1920, a former soldier from his command published an article about it which dredged up best-forgotten memories. But most damaging were all the soldiers from his command who appealed to him for support and advice for overcoming their own struggles. Today, we would say Whittlesey experienced Post Traumatic Stress (PTS).

On November 11, 1921, Whittlesey participated in the burial of the first Unknown Soldier and two weeks later he boarded the British steamship SS Toloa bound for Havana, Cuba. According to the Captain of the Toloa, on the evening of November 26, Whittlesey dined at the Captain’s Table and

appeared in good health and spirits and entered into a lively discussion on football, manifesting an active interest in the Army and Navy football game being played that day…. After dinner he repaired to the smoking salon … and talked with [Mr. Wilmot] for more than two hours on a wide range of subjects. [He,] Mr. Wilmot noted nothing unusual … (Langbart, 2018).

Whittlesey returned to his stateroom shortly before midnight and was never seen again.

The following morning, ship’s crew members found a letter from Whittlesey to the captain asking for his belongings to be thrown overboard and nine letters be delivered to his family and close friends. In addition, he left directions for gratuities to be paid to various crew members and a telegram be sent to his father. The text of the telegram was to read, “Your son Charles Whittlesey jumped overboard and was drowned yesterday. He left letters for you mailed from Habana and notifying Pruyn and Elisha Whittlesey” (Langbart, 2018). In closing, he apologized to the captain for “bother[ing] you with these unpleasant details” (Langbart, 2018). Since the ten letters were not written on ship stationery, it is believed they were written before Whittlesey boarded the ship.

Charles Whittlesey’s cause of death was listed as “drowning at sea by own intent” (Langbart, 2018).

Author’s Note: Two other men of the Lost Battalion, Captain George McMurtry, commander of the 2nd Battalion, and Captain Nelson Holderman, both of whom survived the war, were also awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions during those same five days. During his final mission for the Lost Battalion, carrier pigeon Cher Ami was shot through the breast and the leg before delivering his message, in a capsule hanging from his other leg. Although his time in service was over, doctors worked to save his life, even fashioning a prosthetic leg for him. He is now part of the Price of Freedom exhibit in the National Museum of American History in Washington D.C. Harvard School of Law classmate, Theodore Roosevelt Jr. would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944.

Sources:

Durr, E. (2018, October 2). New York City Draftee Soldiers Made History as the Lost Battalion in October 1918. Retrieved from https://api.army.mil/e2/images/2018/10/02/53184/original.jpg

Langbart, D. (2018, December 11). Aftermath of War: A World War I Hero Lost at Sea: The Death of Charles Whittlesey, 1921. Retrieved from https://text-message.blogs.archives.gov/2018/12/11

Williams College (n.d.). Gargoyle Society. Retrieved from Gargoyle Society – Center for Learning in Action (williams.edu)

*****

Kris Cotariu Harper, EdD, is an Army wife and the daughter of two WWII Navy Veterans. She is an educator and trainer who often writes and speaks on values demonstrated by Medal of Honor recipients.

*****

Further Reading:

Snapshot of Charles Whittlesey’s military record: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/40933867

The Operation of the So-Called “Lost Battalion”, October 2 to 8, 1918, prepared by the Historical Section of the Army War College, August 1928: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/301662

The Lost Battalion of World War I, by Jessie Kratz, Pieces of History blog, National Archives, 21 July 2017: https://prologue.blogs.archives.gov/2017/07/21/the-lost-battalion-of-world-war-i/