Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

In 1862 Major General Ormsby M. Mitchel, commanding Union troops in middle Tennessee, devised a plan to capture Chattanooga, Tennessee, a water and railway junction important to the Confederacy. Mitchel reasoned that capturing Chattanooga would deprive the Western Confederacy of access to the Ohio and Mississippi river valleys. However, he knew that the Southern army would be able to reinforce Chattanooga easily by moving troops from Atlanta by way of the southern railroad system. Those reinforcements would quickly outnumber Mitchel’s forces, which would have more difficulty maneuvering because of the natural water and mountain barriers around Chattanooga. Mitchel would have to figure out a way to neutralize the Confederates’ ability to move reinforcements into position if he had any hope of achieving his goal.

A civilian scout and occasional spy named James J. Andrews had an idea that would enable Mitchel to do just that. Using a small group of volunteers, Andrews proposed a raid that would destroy the Western and Atlantic Railroad, cutting off the Confederate army’s ability to move any supplies or reinforcements from Atlanta to Chattanooga. Andrews presented a convincing case, and Mitchel, after considerable thought, gave his approval. The participants were destined to become known as Andrews’ Raiders. Their raid would become best known as the Great Locomotive Chase.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

As with many plans, Andrews’ was simple in theory but complex in how it could be achieved. While Mitchel moved his troops to Chattanooga, Andrews and his men would steal a train on its run towards the city, stopping periodically to destroy tracks, bridges, switches, and telegraph lines. Having accomplished that, the raiders would cross through Mitchel’s lines and rejoin the Union army.

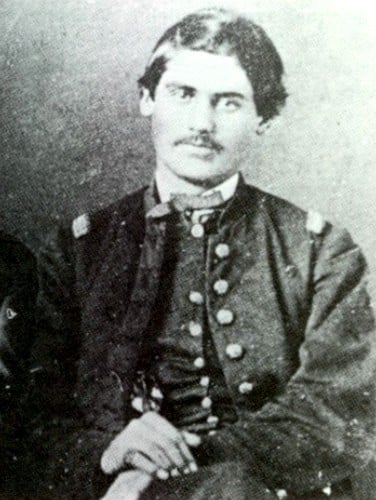

Traveling in groups of twos and threes while dressed as civilians to avoid rousing suspicion, Andrews and fellow civilian William Hunter Campbell, along with 22 volunteer Union soldiers, made their ways to their rendezvous point in Marietta, Georgia. One of those volunteers was Jacob Wilson Parrott, a private from the 33rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry’s Company K. Parrott knew, as well as the others, that if a soldier was captured wearing civilian clothes, he would be hanged as a spy. Still, the mission seemed simple enough, so Parrott dismissed the thought.

The group moved to the village of Big Shanty, Georgia, chosen because they believed that Big Shanty did not have a telegraph office that the Confederates could use to alert others. Big Shanty also had facilities for refueling and adding water, both of which would be needed for a steep grade north of the town.

On April 12, 1862, Andrews and his raiders swung into action, commandeering a locomotive known as the General and its three boxcars, moving northward toward Chattanooga. Along the way, they stopped periodically to tear up track, switches, and bridges, inflicting as much damage as possible, including cutting telegraph wires. With the telegraph wires cut, the Confederates could not alert troops ahead to stop the General, so a pursuit began. The General’s conductor, William Fuller, and two others began chasing the raiders, first on foot, then by a handcar.

When Andrews and his men came upon a locomotive on a siding, they considered destroying it so their pursuers couldn’t use it. However, the presence of a large work party changed their mind. Even though the Raiders were better armed, a firefight would take valuable time that could allow the pursuers to catch up. The General pushed on. Along the way the General was shunted onto a siding to allow other scheduled southbound trains to pass. Knowing his pursuers would be gaining ground, Andrews convinced the station master that he was carrying badly needed ammunition to troops at Chattanooga, under direct orders from General P.G.T. Beauregard. The station master quickly had them on their way.

Delayed a second time at the junction at Kingston, Andrews tried to use his ammunition story again, but was thwarted when the station master informed him that the approaching train had a red flag on its last car, indicating that a second train was following. The General would have to wait until the second train passed. The one-hour delay enabled the pursuers to gain valuable time and distance, and Andrews was able to pull out of the station just minutes before the Confederates arrived. At the station, Fuller took a locomotive named the Yonah, then switching to the William R. Smith shortly after.

Having a locomotive enabled Fuller to keep pace with Andrews until he was stopped once again by missing track, track that Andrews and his men had pulled out. Undaunted, Fuller and his men resumed the chase on foot until they were past the destroyed sections of track. Reaching good track once again, Fuller commandeered another locomotive, the southbound Texas. Not wanting to waste precious time turning the locomotive around, he resumed the pursuit with the Texas running in reverse, pushing its tender in front of it.

With the Texas so close, there was no longer time for Andrews and his men to stop to tear up track or cut telegraph wires. Finally, just 18 miles from Chattanooga, the raiders abandoned the General and scattered. All were captured within two weeks, and Mitchel’s effort to capture Chattanooga would ultimately fail.

The raiders were tried in military courts and found guilty of “acts of unlawful belligerency.” Andrews was hanged, as were seven others who were taken to Knoxville. Fearing the same fate, Parrott and the remaining raiders made a daring escape. Eight succeeded. Parrott and five others did not. Held as a prisoner of war, Parrott was beaten more than 100 times in an effort to get him to divulge more information about the raiders’ intentions. Each time he refused. The POWs were eventually released in a prisoner exchange.

On March 25, 1863, the six raiders who had been recaptured were awarded a newly approved medal to be awarded for valor. Jacob Wilson Parrott became the first recipient of that coveted award, the Medal of Honor, by virtue of the torture he had been subjected to as a prisoner. Later, all but three of the remaining raiders were also presented with the award, except for Andrews and Campbell who, as civilians, were not eligible.

On December 22, 1908, Parrott suffered a heart attack and died while walking near his home in Kenton, Ohio. He was buried in Grove Cemetery, located in Kenton at the corner of State Route 309 and the road that carries the name of the first ever recipient of the Medal of Honor: Jacob Parrott Boulevard.

Today, the hijacked locomotive, General, is on display at The Southern Museum in Kennesaw, Georgia. The Texas, the locomotive used to give chase, is on display at the Atlanta History Center in Atlanta, Georgia.

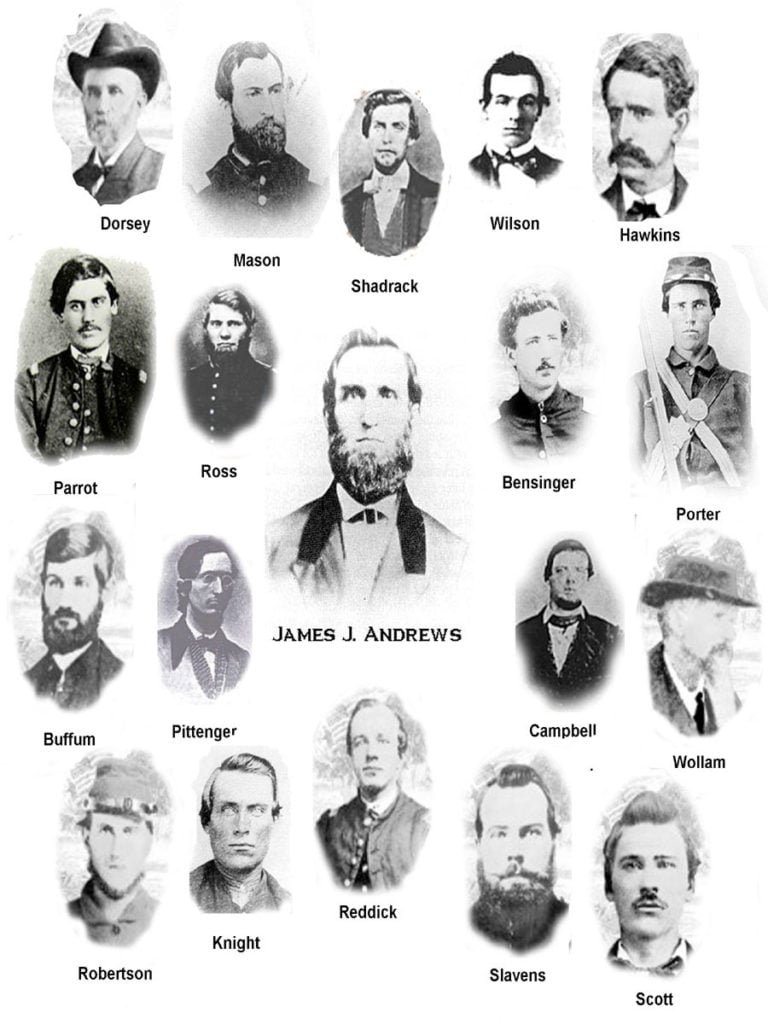

Members of the Andrews’ Raiders

Further Reading