Congressional Medal of Honor Society

Blog Posts

Captain William W. Galt: “Always Out In Front”

Seventy-seven years ago, Medal of Honor Recipient William W. Galt died in his moment of valor on May 29, 1944.

This piece was written by Lowell Silverman as part of the Stories Behind the Stars project (https://www.storiesbehindthestars.org/), with the goal of eventually honoring all 400,000 American service members who were killed during World War II. Additional tributes by the author can be viewed here. Some content in this article comes from letters Galt wrote home during the War and are used with the permission of Galt’s nephew, Erik Gustafson.

We share it here as a way to keep alive Captain Galt’s memory.

Captain William W. Galt (December 19, 1919 — May 29, 1944)

By Lowell Silverman

Author’s note: This article incorporates some text from my article “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters,” first published on the 32nd Station Hospital website on March 25, 2020.

Family and Early Life

William Wylie Galt was born in Geyser, Montana, the son of Errol Fay Galt (1889–1975) and Florence Eleanor Galt (née Johnson, 1893–1973). His father was a bank cashier at the time of William’s birth, though he later became vice president and eventually (in 1947) president of the First National Bank in Great Falls. Galt’s mother had been a schoolteacher before becoming a housewife after her marriage.

Known as Bill (and later as Ace to some of his fellow soldiers), Galt had two older sisters, two younger sisters, and a younger brother. He was Catholic.

Galt’s nephew, Erik Gustafson wrote:

“During his youth, Bill developed a love for ranching and the beautiful ranching country surrounding Geyser. He often worked on the ranches his father managed, as well as the ranches of his father’s friends and clients, and it was at these ranches that he learned the life of a cowboy. It became his lifelong dream to one day own his own ranch and raise cattle.”

In 1933, the Galt family moved from Geyser to Great Falls; William graduated from Great Falls High School in 1937. The following year, he entered Montana State College, where he studied animal husbandry. Galt was a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps cadet, and a member of Scabbard and Blade. One of his close friends in R.O.T.C. was Luther Sidney Gustafson (1920–1943). Known as Sid, Gustafson was destined to become Galt’s brother-in-law posthumously. (After they were commissioned, the two were stationed together stateside but assigned to different units once they arrived in the United Kingdom.)

Early Military Career and North Africa

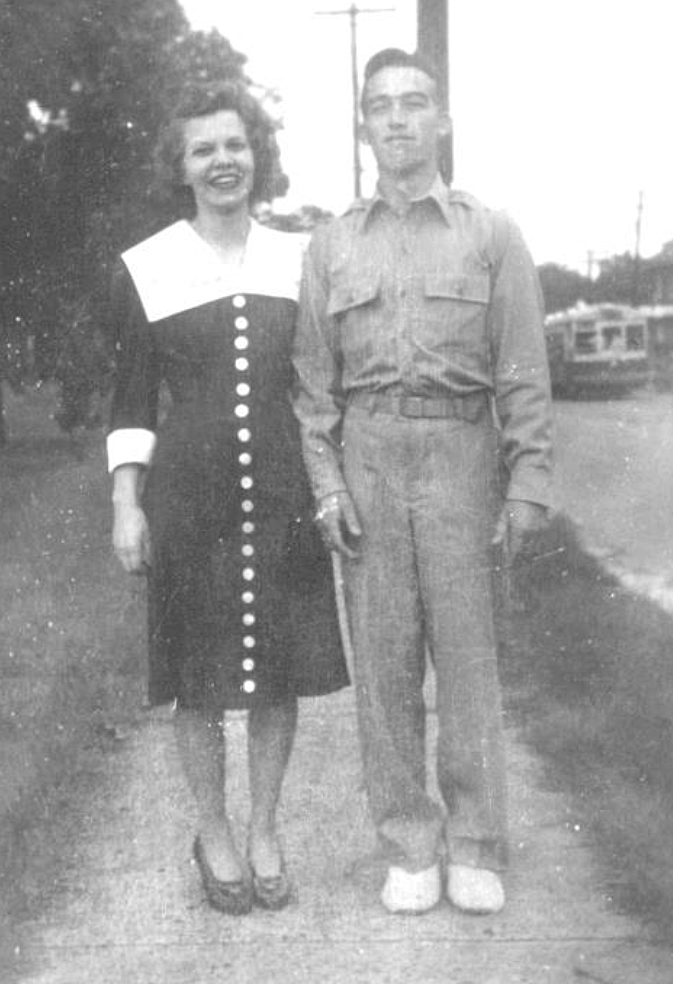

Galt was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant in the U.S. Army upon graduating from college and went on active duty on June 25, 1942. He was briefly stationed at Fort Douglas, Utah before he was transferred to Camp Joseph T. Robinson, Arkansas. On July 24, 1942, Lieutenant Galt married a college classmate, Patricia Ann Sandbo (later Hansen, 1920–2013) in Little Rock, Arkansas.

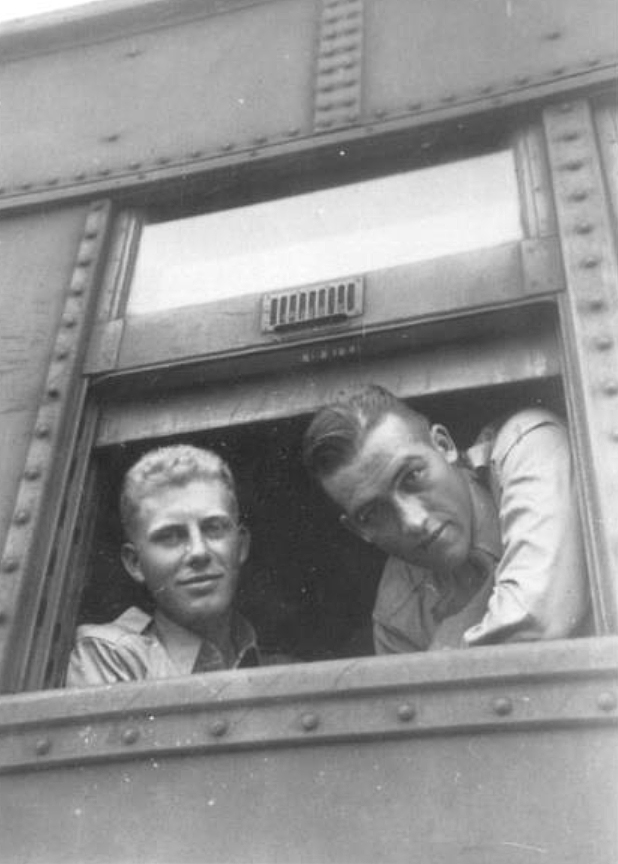

On October 2, 1942, 2nd Lieutenant Galt boarded a train bound for Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, a staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation. He didn’t have long to wait, shipping out on October 5. After arriving in England, Lieutenant Galt joined Company “A,” 168th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division. The 168th Infantry was an Iowa National Guard unit that had been federalized on February 10, 1941. The Regiment had been overseas since April 30, 1942.

After amphibious training in preparation for Operation Torch, Galt’s division shipped out from the United Kingdom. The 168th Infantry Regiment landed in Algeria on November 8, 1942. Though they swept aside token resistance by Vichy French forces cooperating with the Axis, there was tough fighting ahead in Tunisia.

On January 31, 1943, Galt’s company was traveling by truck when they were attacked by a group of German Messerschmitt Bf 109s which inflicted heavy casualties. The following day, during the Battle of Sened Station, the 168th Infantry Regiment faced German and Italian ground forces for the first time. Although the engagement ended in victory for the Americans, the regiment was devastated during the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid two weeks later. Galt’s 1st Battalion alone avoided the encirclement that befell 2nd and 3rd, but the regiment lost close to half its strength.

Galt’s letters home—transcribed by his nephew, Erik Gustafson—reveal Galt’s transformation from an eager young officer into a hardened combat veteran. Despite the setbacks of the previous two months, Lieutenant Galt was cheerful when he wrote his family on March 25, 1943:

“Don’t worry over me because I’m really in very fine health and in good spirits. The fear that gripped each and every one of us last month is now gone or at least well hidden. Reminds me of the fear you or at least I had of a new horse and then gradually as you became more accustomed to each other the fear gradually slips away then you gradually try to make the horse respect you and do your bidding. That is us in a nutshell. Now our fear is gone and our one hope is to wipe the Germans from North Africa and the quicker the better.”

2nd Lieutenant Galt led his platoon during battles at Fondouk, Hill 609, Eddekhila, and Chouigui. An April 13, 1943 letter revealed a potential close call during the Tunisian campaign:

“Did I write and tell you of my ‘day in foxhole’ with 3 Germans. […] Don’t know which of us were more surprised. As I jumped over a ridge about 25 ft away from Machine Gun nest at any rate they stuck up their hands after throwing machine gun down and yelled ‘Don’t shoot comrade’. As things were warm about then I also piled in foxhole and it was long after dark before I could inch my way back to our lines. All told 1st Pl. Co A. 168th Inf. took 17 prisoners, 2 machine guns and a 40 MM field piece on that day.”

Galt was promoted to 1st lieutenant with a date of rank of May 5, 1943, though word did not reach him until May 12. Galt became the executive officer of Company “A” towards the end of the Tunisian campaign following the death of a good friend, 2nd Lieutenant Eugene D. Wilmeth (1921–1943). Wilmeth had been killed by an artillery shell on May 7, 1943, the last day the unit was in combat in North Africa. Galt wrote on August 8, 1943 that Wilmeth had been standing just 20 yards away when he was killed. In a June 23, 1943 letter, Galt wrote that of the 35 officers in his battalion who arrived in Algeria in November 1942, just seven were left. The others had been killed, wounded, or transferred.

Galt’s regiment spent the summer of 1943 training and recuperating from the ordeal of the Tunisian campaign. On August 7, 1943, Lieutenant Galt learned from a casualty list printed in Life magazine that his good friend (and future brother-in-law) 2nd Lieutenant “Sid” Gustafson had been killed in action. They’d run into one another for the last time in North Africa in December 1942; Gustafson was killed in action on April 28, 1943 while serving in Tunisia with Company “G,” 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division.

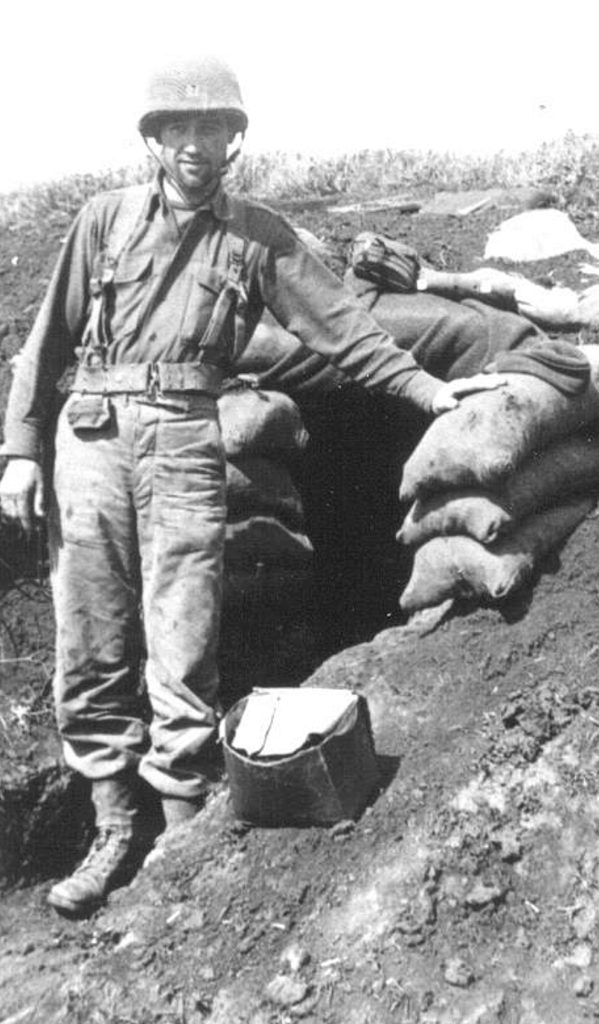

Invasion of Italy

In September 1943, Lieutenant Galt’s unit shipped out for Italy. The 168th Infantry Regiment landed on September 21, 1943, about two weeks after the invasion began. The following month, his unit returned to combat at the infamous Volturno River. 1st Lieutenant Galt earned the Silver Star Medal on November 4, 1943. The citation stated in part:

“Within a short time after the battalion had crossed the Volturno River, the head of the column was delayed by the heavy concentration of mines in their sector. Upon his own initiative and with utter disregard for his own personal safety, Lt. Galt advanced on his hands and knees through the mined area and selected a comparatively safe route to the objective. Lt. Galt’s courageous action enabled the battalion to advance through this mined sector with a minimum number of casualties.”

Lieutenant Galt was slightly wounded that month, though he downplayed it in a letter to his parents:

“Merely a little scratch on my knee that didn’t even put me out of action for a second. Medics, however tagged me so that I could receive a Purple Heart. I will always believe I skinned and cut my knee when I fell on the ground rather than it being cut by shrapnel. So much for that.”

A Letter Home, Thanksgiving 1943

Excerpts from 1st Lieutenant Galt’s November 25, 1943 letter to his parents, transcribed by his nephew, offer particularly vivid insight into the terrible conditions experienced by soldiers in the Italian campaign:

“Thankful today that we are not on lines. Sure would be miserable, of course we had our turn last week and chances are we will go up again Sunday. War doesn’t look too good for us for awhile. We are definitely cracking Jerry’s winter line and tho we go along fairly well, rain, snow, demolitions and such are bound to slow us down. Supplies are a hard thing and this weather, terrain and such makes it that much harder. I believe our Bn. received a citation tho (or will shortly) for our remarkable drive thus far. Jerry is getting harder and harder tho as he gets closer to his homeland. Most soldiers we see now are young and terribly fanatical. Fight much dirtier than the older soldiers we encountered in Tunisia. Took 30 prisoners one night that was all that was left of one of their rifle Co.’s after we had battered them all day with artillery, mortar and our own rifles. Still the typical German though shot at you till the last minute or till he runs out of ammo. then starts crying ‘Komrade’! Sure makes me sore then I could have off and hit them over the head with the butt of a rifle.”

Lieutenant Galt reflected on the losses of the past year:

“Would be a joyous day for ‘A’ Co. men if the old man of the outfit were relieved. Can’t be more than 20 – 25 of us that were eating Thanksgiving dinner in ‘A’ Co. last year. Another year and there will probably be only 5- 6 of us. Surely so few of us cannot be necessary to effort and I doubt if there is a one of us that wouldn’t be a better soldier were we allowed a furlough home to rest and relax and then pick up again. It would be terribly hard to come back again if we ever get home, but I think all of us would be more than willing to do it. I don’t think you could ever realize how much it would mean to be relieved from this duty temporarily.”

Galt continued:

“I’ll be able to tell stories when I get home you would never dream possible. If some one were to write a book of actual warfare in front lines you wouldn’t sell a copy because people would think it a bunch of lies. F.D.R. was right when he said ‘War is Hell’ and I believe it is a mild term to use. Physically I can stand any thing that comes along. It bothers me only slightly to walk miles, to eat poor food and to live in the open. In fact many of these men are better for it, but the mental strain is what gets you. Seeing your men killed, crying for help and you not able to do anything for them. Each succeeding battle I find myself becoming more cautious, more reluctant to drive forward, my mind becoming dazed more easily. I thank God every night that he has given me power so far to hold on to my mind and not return from battle like so many Officers and men I’ve seen.”

Closing his letter, Galt added a postscript:

“This will probably be the Xmas edition of my letters so will take this opportunity to wish you all a Merry Xmas and Happy New Year IT IS STILL Raining.”

Galt spent the first half of December getting some much needed rest off the front lines, including visits to Capri and Pompeii.

Company Commander

On December 18, 1943, 1st Lieutenant Galt assumed command of Company “A,” 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment. The following day, his 24th birthday, Galt received the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. Galt wrote:

“Still kicking and am really happy about finally getting my own Co. to command, also tickled about the two awards received on my birthday. My promotion to Capt. went in 3 days ago so will sweat it out.”

Galt was promoted to captain effective January 5, 1944, though word didn’t reach his unit until January 21. During grueling combat near the Rapido River, Captain Galt was wounded by a German mortar on January 26, 1944.

He wrote to his family from the hospital on February 3:

“Just happened to be sitting in the wrong place at the wrong time and a Jerry mortar shell exploded near me. Got minor pieces in my back, left shoulder, rt. thigh and rt. arm. I was promptly evacuated tho and within 12 hrs. operated on and all shrapnel removed. Since then just sore and stiff. Got it on afternoon of Jan. 26 so you can see I’m already well on road to recovery so please don’t worry.”

Anzio

Captain Galt left the hospital on February 17, 1944 and the following day he returned to his unit (which had been rotated off the front lines). In March 1944, his division was shipped as reinforcements for VI Corps at the Anzio beachhead. Intended to bypass defensive lines near Cassino, German reinforcements had fought the Allied invasion force to a standstill.

Although jovial on the face of it, a letter that Captain Galt wrote to his family after six days at Anzio revealed tremendous strain:

“What a difference this type of warfare is from our usual attacking. Now we can sit back and let Jerry come at us. (If he wishes, which I doubt). My dugout, which is shared jointly by myself and the 1st Sgt. & our assorted equipment is the new 1944 super-deluxe model designed especially to ward off anything up to a direct hit. The dugout is complete to an electric light by which we can better read our maps. Write letters, make coffee at ungodly hours of the night, read and all the other little things one wants to do. We haven’t slept in last six nights, but always catch a few winks shortly after daylight until about 10:00 in the morning, i.e. providing Jerry don’t pick that time to toss in a few shells and rile us up.”

What Captain Galt wrote next would surely have been unthinkable to him a year before:

“I’ve seriously thinking of traveling the short 100 yds to Jerry’s line and making some sort of gentleman’s agreement with him whereby if he don’t shoot, neither will we and also as long as we’re both in this not of our own free will, why not be real friendly whilst fate has put us so close together in such a stable position.”

In an April 2, 1944 (Palm Sunday) letter to his family, Captain Galt wrote of his faith:

“As for praying, every one does just that. Those that didn’t know standard prayers before battle make up their own in an awful hurry and then when things are slacker they grab someone and learn the real McCoy. It is not uncommon to see numerous men as I walk back and forth between gun positions reading a Bible in one hand and the other hand on a trigger of a MG [machine gun]. As I’ve said times before battle is one place where a man realizes that some Greater Power is watching over him.”

In the same letter, Galt reflected grimly on his naivety back when he was a freshly minted 2nd lieutenant:

“18 months ago today Sid and I said goodbye at Little Rock. Feel sorry for Sid. Of all of us that left Little Rock that day only very few of us left overseas. […] Little did I dream when I left Little Rock that I’d be gone this long and still no definite outlook on when I’ll return. I thought that day a year at the very most and I would be back, but it looks now like the 2 yr. mark will be reached with ease. Open the door wide though because one way or another I’ll surely be home by Xmas 1944. Our saying in outfit is ‘Golden Gate in ‘48’ but even I fail to see the joke in that any longer.”

On April 15, 1944, Captain Galt was hospitalized again in Naples. He wrote his family on April 20:

“Seems as though my nervous system has become so bad that I’m imagining pains where there shouldn’t be any! At least that was first diagnosis (and probably right ), but I’m now undergoing various tests and exams to determine possibility if anything is wrong. My complaint is more or less persistent pains in my lower abdominal regions that at times bother me to quite some extent.”

After he was discharged from the hospital on April 29, 1944, Captain Galt became S-3 (operations officer) for 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment. He wrote of his in duties on May 11, 1944:

“The beauty of it as it affects me is this – I no longer have enlisted men to order about or to worry about. In other words, I now look after [myself] and that is all. You can never realize the relief this has on one until you have actually led men in battle. Had ‘A’ Co. been still made up of all the old men I knew I might have said no to the transfer, but times have changed all the personnel except a very few so I’m really not leaving many.”

The Fourth Assault on Villa Crocetta

On May 23, 1944, the long-awaited breakout from Anzio began. Advancing northeast from Anzio, within two days, VI Corps was on the verge of encircling the German Tenth Army as it retreated from the Cassino area. In the most controversial decision of his career, the commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, Lieutenant General Mark W. Clark, shifted the bulk of his forces northwest in order to capture Rome. As a result, VI Corps faced strong German positions in the Alban Hills known as the Caesar Line.

To assist the 168th Infantry Regiment in cracking the Caesar Line, several companies were attached on May 26, 1944, including Company “D,” 191st Tank Battalion and Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion. 1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment took several hills that day, capturing 19 prisoners. Lieutenant Colonel Wendell H. Langdon (1908–1984) became battalion commander that evening.

On May 28, 1944 the battalion began a series of unsuccessful assaults against Villa Crocetta, located southeast of Lanuvio. The Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome stated that:

“On the right the 168th Infantry faced two particularly nasty strongpoints: Gennaro Hill and Villa Crocetta on the crest of Hill 209. As our troops approached either point, they had to cross open wheat fields on the neighboring hills, then make their way across the draws formed by the tributaries of Presciano Creek, and finally attack up steep slopes to their objectives. The German line was marked by a trench five to six feet deep which ran across Hill 209 and on past the southern slopes of Gennaro Hill. Based on this trench and its accompanying dugouts, machine guns were emplaced to command the draws, and mortars were located in close support. At Hill 209 the enemy also had wire nooses, trip wire, and single-strand barbed wire to break the impact of our charge.”

1st Battalion, 168th Infantry Regiment attacked Villa Crocetta twice on May 28, 1944 and once again on the morning of May 29. During the first attack, the battalion had been hit by friendly artillery. Morale was at low ebb following the failed third attack. That time, the battalion’s infantrymen had reached the objective, but once again American artillery fire was poorly coordinated with the attack. A bombardment that had been intended to support the battalion’s advance instead forced them to retreat.

There was little respite for the weary infantrymen, who had been without adequate food or rest for almost a week. Lieutenant Colonel Langdon ordered a fourth attack, scheduled for 1315 hours on May 29, 1944. Unlike during previous assaults, this time the infantrymen had the support of four M10 tank destroyers and three light tanks.

Captain Galt left the battalion command post to observe the fourth assault on Villa Crocetta. In a letter to Captain Galt’s father dated August 25, 1944, Captain William B. Holmes, who had previously commanded Galt in Company “A” during the Tunisian campaign, explained why:

“In the States the S-3 has charge of the training program whereas overseas the emphasis is on the ‘plans’ part of the job. He aids the Bn. Commander in formulating his plans for offense or defense or whatever type of operation is contemplated. In order to do this he must make frequent reconnaissance to get data on the type of terrain over which the operations are to take place and to learn what he can of the enemy dispositions.”

Among the few belongings that Captain Galt had on his person that fateful day were a Catholic medal, a fountain pen, and a set of black rosary beads. His sidearm—possibly a Browning P-35—was not standard issue for an American officer.

Company “B” initially made some progress. According to “The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment from May 1, 1944 to May 31, 1944,” the company “evidently took the enemy by surprise, for they withdrew from their entrenchments on the slope of the hill [203] without firing a shot.” Leaving six American soldiers to hold the position, the rest of Company “B” continued towards Villa Crocetta. They came under fire and were briefly pinned down, but with the support of the American armor, they managed to press on. However, the Germans returned to Hill 203 and dislodged the six-man strong-point, opening fire on the rest of Company “B” with their machine guns.

Companies “A” and “C” were supposed to join the attack around this time. However, according to the 168th Regiment’s history, “After the failure of the third attack on the Villa, Company ‘A’ and Company ‘C’ were approaching the point of complete demoralization.” Only a handful of men from these companies advanced during the fourth attack and those that did were soon pinned down.

A Fateful Decision

Captain Galt spent close to an hour with Staff Sergeant West R. Lyon (1916–1988) of the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion, observing the attack with increasing concern. About 300 yards up ahead, an M10 tank destroyer commanded by 1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie (a platoon leader from Company “C,” 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion) was attacking some German infantry. Jarvie’s crew consisted of Sergeant Robert D. Lightsey (probably gunner), Corporal Elmer F. Park (probably loader), Corporal John F. Perkins (driver) and Private Reamer H. Conner (assistant driver). A radio message went out that a friendly artillery strike on the German position was imminent. Jarvie withdrew and his crew began replenishing their ammunition from Staff Sergeant Lyon’s halftrack.

Captain Galt, 1st Lieutenant Jarvie, Sergeant Lyon, and an unidentified 1st lieutenant had a discussion and Galt decided to personally join the assault. It was a surprising decision, especially in light of Galt’s letter six months earlier stating that “Each succeeding battle I find myself becoming more cautious, more reluctant to drive forward.” A battalion S-3 was not expected to lead infantry assaults. Of course, Galt had been S-3 for less than a month; perhaps his instincts as a long-serving platoon leader and company commander took over. Captain Galt’s nephew, Erik Gustafson, suggested that his uncle felt duty-bound to intervene with his old company pinned down.

Whatever the reason for his decision, Captain Galt advanced along with the tank destroyer and Company “B” infantrymen. At some point (either from the beginning of the new push forward or later, when Jarvie’s crew paused to repair a thrown track and replace a radio antenna hit by enemy fire), Captain Galt boarded the M10.

As the tank destroyer approached the enemy trench line, Captain Galt stood on the rear deck of the M10, firing the .50 caliber machine gun mounted on the rear of its turret. The Germans in the trenches and buildings ahead unleashed a hail of small arms fire at the tank destroyer. The turret provided some protection, but standing behind it, Captain Galt was still partially exposed while firing the machine gun. Technical Sergeant Ervin M. Frey (1919–1991, a platoon sergeant in Company “B,” 168th Infantry Regiment who in one account manned a .50 on another M10 and in another account rode briefly on Jarvie’s before dismounting) spotted an enemy anti-tank gun and notified Captain Galt. Jarvie’s crew destroyed the gun with fire from their 3-inch gun.

The M10 passed through an olive grove and reached a German trench. Captain Galt’s machine gun fire decimated the German infantry, who fled in disarray. One report credited him with killing approximately 40 German soldiers.

It was around 1420 hours when disaster struck. According to the 168th Infantry Regiment history, 1st Battalion’s intelligence officer observed:

“an estimated company of Germans, supported by four tanks, counter-attacking down the valley with bayonets fixed. One of the tanks pulled up behind the Villa and fired a shell through the turret of a tank destroyer, killing the battalion operations officer who had been firing the tank destroyer’s 50 callibre [sic] machine gun at the retreating Germans.”

In a statement dated October 16, 1944, the M10’s driver, Corporal John F. Perkins recalled:

“After we picked up this Infantry Captain, we travelled about one hundred (100) yards before we were hit. The Captain was standing on the back of the Tank Destroyer when he got killed. He was firing the .50 caliber. We were sitting still when the tank [sic] was hit. The shell came through the turret. I saw Lt. Jarvie and Sergeant Lightsey fall to the bottom of the turret. In about four or five seconds, the tank caught fire and I went out the turret on the left side after crawling over them (both of them).”

Captain Galt, Lieutenant Jarvie (1914–1944), Sergeant Lightsey (1911–1944), and Corporal Park (1919–1944) were killed in the German attack. Corporal Perkins (1908–1984) and Private Conner (1923–1998) were badly wounded but managed to escape the burning tank destroyer.

The 168th Infantry Regiment history ruefully noted that the German “counter-attack, supported by tanks, was too strong for the twenty men left to hold the hill.” The surviving American infantry retreated.

Villa Crocetta proved too strong for the 168th Infantry Regiment to take. A fifth attack the following day also failed. It wasn’t until the 36th Infantry Division managed to penetrate the Caesar Line to the east near Velletri that the German position at Villa Crocetta became untenable. Rome fell in turn.

Highest Honors

In the months that followed, letters arrived at Captain Galt’s parents’ house expressing condolences and praise.

A July 20, 1944 letter from Chester Smith relayed a message from one of Galt’s men, Paul K. Swift (1920–2012):

“Please write them for me, tell them that I was with him and all the fellows who had dealings with him thought of him as one of the finest officers. His death was sudden and with no suffering whatsoever. He was a brilliant leader and very cool and sound thinker under fire, and looked out for his men. They all loved him. I shall not throughout the years, if I survive, forget my dear friend and Captain[.]”

His former company commander, Captain William B. Holmes wrote on August 10, 1944:

“I know it is impossible for me to say anything that will ease your sorrow over such a great loss, but I wanted you to know how very much I admired and respected your son, as did all the other officers and men of my command. He made a tremendous impression on me through his leadership, courage, and ability and I will remember him long after I forgotten some of the other officers of my company. He and Lt. Wilmeth stood head and shoulders above the rest.”

A former officer from his company, Lieutenant Norris J. Lorton (1915–1980) wrote on September 8, 1944:

“Knowing Bill as I do, I know that he was on the job out there in front when he got it. That was his way — always out in front. I believe I told his wife when I wrote to her after my return to the States that Bill was a damned fine soldier. I always felt that if I could be just half as good I’d be happy, and I’m sincere when I say that.”

Captain Galt was buried in the cemetery in U.S. Military Cemetery, Nettuno on September 6, 1944. For his actions during the fourth assault on Villa Crocetta, Captain Galt was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor on January 4, 1945; the medal was presented to his widow Pat at Great Falls Army Air Base on February 19, 1945. His remains were disinterred in 1948 and reburied at Mount Olivet Cemetery in Great Falls, Montana. That same year, Galt’s widow remarried to Wendell Hansen (1924–2008), with whom she raised three sons.

Notes

Posthumous Brother-in-Laws

Although Galt was close friends with 2nd Lieutenant Sid Gustafson, they did not become brothers-in-law until 1952, after their deaths. That year, Galt’s younger sister Patricia Jane Galt (1927–2012) married Gustafson’s younger brother Raymond Walter Gustafson (1925– 2014).

Captain Galt’s Catholic Medal and Sidearm

The inventory of personal effects on Captain Galt’s body listed “religious medal (St. Christopher)”. However, in a January 19, 1944 letter, Galt told his mother “I wear continually around my neck the medal you sent (St. Benedictine?) last summer. (Grandma sent me similar one I received a few days ago). In fact I’m becoming so attached to the medal if I should lose it I would not feel safe at all.”

Just about the only thing that can be said with certainty about Captain Galt’s pistol is that it wasn’t a standard issue Colt M1911. In a December 13, 1943 letter to his older sister Edna Ann, Galt mentioned using a German Luger that he took from “one of the dirty devils.” Of course, he might not have been using the same weapon five months later. In a statement dated October 16, 1944 reproduced in Captain Galt’s I.D.P.F., 2nd Lieutenant West R. Lyon of the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion described Galt’s pistol as “a German P-35 automatic of a Belgian make.” That would suggest it was the Belgian Browning P-35, or less likely, a similar Polish pistol that the Germans referred to as the P 35(p). Oddly enough, a statement dated August 4, 1944 and written by Sergeant Charles C. Lee, Headquarters Platoon, Company “A,” 168th Infantry Regiment, stated that there was a revolver on Captain Galt’s body. Another oddity in Sergeant Lee’s statement was that when he visited the battleground on June 3, 1944, Captain Galt’s body was “75 yds from an American tank and 800 yds south of Villa Crochetta.” [sic]

When Did Captain Galt Board the M10?

Until recently, Captain Galt’s Medal of Honor citation was the only source of information about his final battle readily available to the general public. It was based on an account by 1st Lieutenant Francis W. Chandler (1917–2002). Chandler was the regimental awards and decorations officer. Although he was identified as an “eyewitness” in a press release by the War Department Bureau of Public Relations, I believe Chandler saw very little if any of Galt’s actions during the battle.

Exactly when Captain Galt boarded Lieutenant Jarvie’s M10 is unclear; it’s possible that he advanced part of the way with the rest of the infantrymen on foot. Chandler’s statement was that “When the crew was reluctant to go forward, Captain Galt jumped on the tank destroyer and ordered it to proceed [sic] the attack.”

However, the M10’s driver, Corporal Perkins stated that Captain Galt had been aboard only briefly, during the last 100 yards he’d driven before the tank destroyer was hit. Similarly, according to the assistant driver, Private Conner’s October 16, 1944 statement:

“We started to move up on some Jerry Infantry about 50–60 yards away. They radioed in and told us they were going to lay an artillery barrage in front of us. So we pulled back about 300 yards and waited about a half an hour. Meantime we transferred some ammo from Sergeant Lyon[’]s [half]track to ours. We moved up again and we was [sic] crossing a ditch and threw a track. We finally got the track on with a bar, Sergeant Lightsey put a new antenna on (broken one was shot off). I’m not sure when that Captain got in with us, but I believe it was right after that when we [went] up over a small bank grade like and hardly made it there and along a olive grove that we saw a few Jerries there and we turned in a grove and started through and all the Jerries were ditched and we moved up around 20 yards and cleaned up the Infantry and then we moved up another 20 yards where got hit.” (Italics are the author’s.)

However, they undoubtedly had to have exited the vehicle in order to repair the thrown track. That Private Conner believed Captain Galt got on board after the repairs suggests that he did not see Captain Galt manning the .50 when he got out to make the repair. The two accounts could potentially be reconciled if Captain Galt rode the M10 for a period, alighted while the crew repaired the track, and then got back on, though there is no evidence suggesting that is the case.

Unfortunately, West R. Lyon’s statement doesn’t explicitly answer the question:

“Lieutenant Jarvie and I and Captain Galt and another 1st Lieutenant (who later took over in Captain’s Galt’s place), moved out and attacked the hill and approximately three minutes before he was hit he was standing on the M-10 firing the machine gun. About ten minutes later the tank was burning.”

Clearly, Lyon was saying they all advanced together and he later observed Captain Galt firing the machine gun aboard Jarvie’s M10, but not that Galt was aboard the tank destroyer from the start.

Medal of Honor Citation Discrepancies

Understandably, the Medal of Honor citation is designed to present Captain Galt in the best possible light, but some parts of the story are of dubious accuracy. In addition to the matter of when Captain Galt boarded the M10, disputed points in the citation, which I discuss in further detail in my article “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie” are:

- Galt’s action followed “two unsuccessful attacks by his battalion” (rather than three).

- Jarvie’s M10 was the “lone remaining tank destroyer” (since the regimental history stated that “Three tank destroyers and two tanks reached the objective”).

- Jarvie’s crew “refused to go forward” (not substantiated by any other known written account).

- Captain Galt “manned the .30-caliber machinegun in the turret of the tank destroyer” (rather than firing a .50 caliber machine gun while standing on the rear deck).

- Captain Galt “located and directed fire on an enemy 77-mm antitank gun” (as opposed to Technical Sergeant Frey spotting it).

Special thanks to Erik Gustafson for biographical information about his uncles, as well as the use of letters and photos. Thanks also to Rob Hadleman, Dennis Victor Dupras, and Steve Cole for their assistance in untangling the confusing and contradictory details surrounding the fourth assault on Villa Crocetta.

Bibliography

“2LT Luther Sidney Gustafson.” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/56247410/luther-sidney-gustafson

“Congressional Medal of Honor Awarded Captain Galt.” Great Falls Tribune, February 20, 1945. Pg. 1. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/66952682/galt-moh-ceremony/

Fifth Army History Part V: The Drive to Rome, Chapter VII (Expansion of the Beachhead Attack) . Publisher unknown. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/5th-army-history-part-v-chapter-vii.pdf

Galt, William W. Individual Deceased Personnel File. National Personnel Records Center. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/galt-william-wylie-wwii-army-idpf.pdf

Gustafson, Erik. “Captain William Wylie Galt Biography and Letters Home from WWII.” Unpublished article courtesy of Erik Gustafson.

“Headquarters 168th Infantry S-3 Journal.” May 29, 1944. Records of the 168th Infantry Regiment in World War II Operations Reports, 1940 – 1948. Records Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905 – 1981. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland.

“The History of the 168th Infantry Regiment from May 1, 1944 to May 31, 1944.” Records of the 168th Infantry Regiment in World War II Operations Reports, 1940 – 1948. Records Group 407, Records of the Adjutant General’s Office, 1905 – 1981. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland. https://32ndstationhospital.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/168th-infantry-regiment-history-may-1944.pdf

Montana, Birth Records, 1919-1986. Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, Helena, Montana. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61591/images/48414_1220706333_0212-00132

“Patricia Hansen.” Great Falls Tribune, February 24, 2013. Pg. 2, Section M. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/46977151/patricia-ann-hansen-captain-galts/

Press Releases and Related Records, compiled 1942–1945. Records Group 337, Records of Headquarters Army Ground Forces, 1916–1956. The National Archives at Washington, D.C. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/3026/images/40445_647661_0475-01300

Pulaski County, Arkansas, Marriages 1838-1999. Pulaski County Clerk, Little Rock, Arkansas. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/61797/images/61797_b929844-01182

Silverman, Lowell. “1st Lieutenant John S. Jarvie: Jack in the Alice Griffin Letters.” 32nd Station Hospital, March 25, 2020. Updated December 6, 2020. https://32ndstationhospital.com/2020/03/25/1st-lieutenant-john-s-jarvie-jack-in-the-alice-griffin-letters/

Stanton, Shelby L. World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939–1946. Revised ed. Stackpole Books, 2006.

The Story of the 34th Infantry Division: Louisiana to Pisa. Information and Education Section, Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army, c. 1944.

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1920. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6061/images/4313236-00830

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1930. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/6224/images/4610689_00760

United States of America, Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1940. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/2442/images/M-T0627-02214-00774

Article last updated on January 7, 2021.