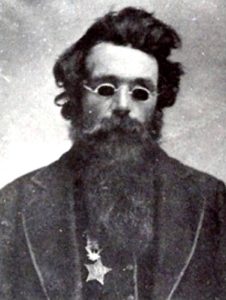

Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

The Battle of Gettysburg is arguably the best known and most written about battle of the Civil War. From July 1 to July 3, 1863, Union Major General George Meade’s 93,921 troops took on 71,699 of their counterparts under Confederate General Robert E. Lee. There would be more than 51,000 casualties, making Gettysburg the bloodiest single battle of the war. The Union victory ended Lee’s invasion of the North and, even though the war would last another two years, was instrumental in destroying the hopes of the South to become an independent nation. Sixty-four Medals of Honor were awarded, with one of them presented to Sergeant Jefferson Coates of the 7th Wisconsin Infantry. The following is his story.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

Jefferson Coates, also known as Francis Jefferson Coates, was born in Boscobel, Grant County, Wisconsin, on August 24, 1843, the oldest of three children born to William Coates and Cynthia Cain. Anxious to join the Union army when the Civil War broke out, he enlisted just five days after turning age 18, joining on August 29, 1861. He mustered in on September 2, 1861, as a corporal in Company H of the 7th Wisconsin Infantry, which eventually became part of the famed Iron Brigade.

Coates saw his first action at Second Bull Run, nearly a year after mustering in. That battle had resulted in a Union defeat and Coates lost several of his friends in the battle. The Maryland Campaign followed, with several more companions becoming casualties. Coates himself was wounded at the Battle of South Mountain on September 14, 1862, one of the Union’s 2,325 casualties. Despite the pain of his wound, Coates was proud of the part he had played in the Union victory.

Less than a week later, the 7th Wisconsin fought at Antietam before a lull of nearly nine months. Coates welcomed the break in the action, using the time to fully heal from his South Mountain injury. Then came the march to Gettysburg where his life would be changed forever.

On July 1, 1863, Coates, the 7th Wisconsin, and the rest of the Iron Brigade clashed with part of Brigadier General James J. Archer’s brigade on McPherson Ridge at Gettysburg. Fighting was brutal, and Archer was captured, the first Confederate general officer taken captive since Robert E. Lee had taken command of the Army of Northern Virginia.

The 7th Wisconsin fought valiantly, and none fought harder than Coates. Fighting at close quarters became hand-to-hand combat. Bayoneted in his side, Coates refused to stop fighting. His courage was inspirational for his comrades, and he was credited with sparking the effort that pushed Archer’s men off McPherson’s Ridge. At the peak of the fighting, however, he was shot in the face. Unable to see, he could only listen helplessly to the din of the battle. A compassionate Confederate officer, perhaps having seen the courage with which Coates had fought, guided the 19-year old to the safety of a nearby tree. He was found after the fighting moved to another area, still leaning against the tree, his sight permanently gone. Moved to the Satterlee Hospital in Philadelphia, he was discharged for disability on September 1, 1864.

Following his discharge Coates adapted to his new situation. He learned to read braille. Needing a means of supporting himself, he took up the trade of broom making. On June 29, 1866, his heroics at Gettysburg earned him the Medal of Honor. His citation recognizes the ferocity with which he fought, stating, “Unsurpassed courage in battle, where he had both eyes shot out.”

On April 21, 1867, less than a year after receiving the Medal of Honor, he married Rachel Sarah Drew and moved to Dorchester, Nebraska, where he and Rachel reared five children. He fell ill with pneumonia at age 36 and passed away on January 27, 1880. He was laid to rest in the Dorchester City Cemetery.