Samuel McConnell: On the Advance

The Civil War was nearing its end, and now-confident Union generals saw their opportunity to deal a death blow to Southern forces in the deep south. On April 8, 1865,…

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina announced it would no longer be a part of the United States. Over the next several months, state after state in the South followed suit, until 11 states had seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America. As each state seceded, many of her native sons who were serving as officers in the service of the Union resigned their commissions and declared their allegiance to the Confederacy. The smallest branch of the Union’s military, the Marine Corps, lost nearly a third of its officers when 20 of the 63 officers left. Nearly all of them formed the bulk of the leadership of the Confederate Marine Corps. That movement set the stage for an historical clash at the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia.

On May 4, 1862, Union troops under General George Brinton McClellan began advancing toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. In response, Confederate forces rushed to defend the capital. As part of that effort to stop McClellan, the Confederates abandoned the Norfolk Navy Yard, destroying anything that had any military value before leaving. Two months earlier the CSS Virginia had fought the USS Monitor in the epic battle of ironclads at Hampton Roads. On May 11, however, she was set afire to prevent her from falling into Union hands. The fire gradually worked its way to the magazine, causing an explosion that left the Virginia in pieces.

The loss of the historic vessel left the James River effectively undefended by the Confederates. Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, recognizing this, directed that a Union squadron be sent up the James River to attack Richmond by water. That plan was thwarted at Drewry’s Bluff by a determined force of Confederate sharpshooters and artillery. The Union squadron was forced to withdrawal, and Richmond remained in Confederate hands for three more years.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

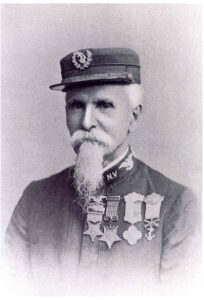

John Freeman Mackie was born October 1, 1835 in New York. As an adult he worked as a silversmith until his enlistment in the Marine Corps on April 24, 1861, just 12 days after the firing on Fort Sumter, SC. He took his oath for enlistment at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and was assigned to the USS Savannah. He transferred to the USS Galena on April 1, 1862.

Under the command of Commander John Rodgers, Jr., the USS Galena led a squadron of four other vessels up the James River on May 15, 1862. Those four other boats were the ironclads Monitor and Naugatuck, and the wooden gunboats Aroostook and Port Royal. The Galena was also an ironclad, with 3” thick heavy iron plating protecting her sides.

On board the Galena, Marine Corporal Mackie felt excited but confident, knowing that capturing Richmond would likely bring the war to a close, a victory made likely by the minimal defenses on the James River that could be put up by the Confederates. In addition to taking Richmond, the squadron had been ordered to disable any shoreline Rebel batteries they may encounter, a task that would hardly prove daunting, and any obstructions placed in the river could easily be swept aside. Of little concern to Mackie and his shipmates, General Robert E. Lee’s troops had chosen a location on the James to make a stand. That site, Fort Darling, sat on Drewry’s Bluff, a promontory some eight miles south of the Virginia capital. Had those aboard the Union boats been more familiar with that area, however, their lack of concern over a possible encounter with the Confederates would have been replaced with a feeling of dread. Now, Fort Darling lay not far ahead.

Situated about 100 feet above the river on a bend, the Rebels held a perfect defensive position. The view in both directions stretched more than a mile, rendering any stealthy water approach impossible. The fort was manned by a battalion of artillery, along with three heavy guns and several regiments of infantry. Further, 160 Confederate Marines took a position on the river bank. On the opposite side of the river, the crew of the Virginia, still smarting over the loss of their ship and giddy with the thought of seeing the Monitor again, manned their cannon. The Virginia’s Marine detachment served as sharpshooters.

As the small flotilla steamed upriver, their plan was for the Galena to fire her six guns on the fort, destroying it and rendering it a non-factor. While that was being done, the remaining four boats would slip past what was expected to be a token defense and continue upriver.

The sun was just burning away the early morning fog when the fort came into view. Some 600 yards from the fort, the Galena took a position in the narrow channel that placed her perpendicular to the current and readied her guns. The Southerners immediately took the offensive, firing their guns before the Galena could start shelling the fort. The battle was on, and would last for several hours.

Shot and shell rained down on the Galena, surprising Mackie and the rest of the crew. Rather than simply steaming past the fort and continuing toward Richmond, the rest of the squadron found themselves desperately fighting . Then, the main gun on the Naugatuck malfunctioned, taking her out of the fight. Remarkably accurate artillery fire struck the two wooden gunboats, forcing them to retreat. The Monitor maneuvered to a point just above the Galena, her captain hoping the combined fire of the two would silence the guns on the bluff. Once in position, however, the Monitor’s guns could not be elevated enough to strike the top of the bluff. Her well-intentioned captain had no choice but to withdraw.

The Galena continued the fight alone, with Mackie and the rest of the Marine contingent focusing on those manning the guns, rather than on the guns themselves. Soon, two of the enemy guns were silenced. The remaining Rebel guns continued their deadly fire, however, and many of the Galena’s crew were wounded or killed. The three-inch armor that was thought to be sufficient to protect them soon proved to be of little help.

The Marines on both sides poured a deadly barrage on one another. The Confederate artillery proved to be too much, and it wasn’t long until the Galena’s heavy guns were disabled and her decks were covered in gore. Body parts were strewn in all directions, and the blood made the footing so difficult that the Marines found that they could no longer aim accurately.

Mackie realized that what had been expected to be little more than a skirmish was now a battle for survival. Taking charge, he began moving the wounded aside and started to throw sand on the slippery deck. Seeing Mackie’s actions, the 12 Marines under his command followed, and within minutes Mackie and his men had the disabled guns serviceable again. Their first volley blew up one of the fort’s casemates and knocked a gun out of service.

Mackie and the rest of the Marines manned the guns until their ammunition was nearly gone. Rodgers realized that their mission would not be accomplished, and reluctantly he ordered the Galena to withdraw. The Battle of Drewry’s Bluff marked the first and only time in our nation’s history that U. S. Marines went into combat against former Marines. For now, Richmond remained in Confederate hands. When McClellan’s troops also were repulsed, the Southern capital once again stood secure.

On July 8, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles boarded the Galena, now anchored at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia. After inspecting the damage, Lincoln marveled aloud that anyone had survived the onslaught. Rodgers then called three of the crew forward for recognition as heroes. One of those three was Corporal Mackie, the other two were Quartermaster Jeremiah Regan and 1st Class Fireman Charles Kenyon. Lincoln thanked each of the three for their gallantry, then turned to Welles and ordered that each of the three men be given a promotion and be awarded the Medal of Honor. Lincoln’s action marked the only time that a president recommended troops for the Medal. There was also one more “first”; Mackie became the first active Marine to be accorded the honor.

Mackie’s citation read: On board the U.S.S. Galena in the attack on Fort Darling, at Drewry’s Bluff, James River, on 15 May 1862. As enemy shellfire raked the deck of his ship, Cpl. Mackie fearlessly maintained his musket fire against the rifle pits along the shore and, when ordered to fill vacancies at guns caused by men wounded and killed in action, manned the weapon with skill and courage.

Mackie remained on the Galena until November 1, 1862, when he transferred to the Norfolk Navy Yard. In June 1863 he was assigned to the USS Seminole, and it was on this ship that he received his Medal of Honor. He was discharged on August 23, 1865 at the Boston Navy Yard and moved to Philadelphia, where he died on June 18, 1910. He was buried in the Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania. A marker has been placed at Drewry’s Bluff commemorating Mackie’s actions.

If you would like to support the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s mission to preserve the legacy of the Medal of Honor and its Recipients, please consider donating to our foundation here.