Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

For those who have seen the movie ‘Glory,’ the story of the assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 is a familiar one. Situated on Morris Island in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, Fort Wagner had already been unsuccessfully assaulted by the Union army a week earlier. Known as Battery Wagner in the South, that earlier assault had resulted in heavy Federal losses, partly because of heavy artillery fire, but also because the approach to the fort was a strip of beach so narrow that only one regiment could attack at a time. The chance for success was further complicated by the shallow moat that surrounded the fort, a moat that included sharpened palmetto logs and underwater spikes.

On July 18, 1863, Union Brigadier General Quincy Gillmore had the unenviable assignment of leading a campaign against Charleston. Charleston had been looked at as a symbol of the rebellion by Northerners, with the city’s Fort Sumter having been taken from the Union army by Confederate troops in April, 1861 in an attack that is considered the official beginning of the Civil War. If Gillmore could capture Fort Wagner and Charleston, Union officials reasoned, it would gain some measure of revenge while demoralizing the states in rebellion.

Gillmore began his assault early in the morning with an artillery barrage from four land-based batteries, followed shortly by a similar bombardment from 11 ships that lasted most of the day. Not long before sunset, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw led the 54th Massachusetts, the first African-American regiment raised in the North, in the attack on the fort, which had been constructed of sand and earth. The effort was a blood bath for the regiment and those that followed, and within two hours the assault had been repelled and the fort remained in Confederate hands.

Although a resounding Federal defeat, the performance of the 54th Massachusetts that day dispelled the theory that black men could not fight as well as their white counterparts. Their actions led to recruiting additional black troops.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

The bombardment was over. The men of the 54th Massachusetts began their march, each man aware he may not return. They also knew they carried the weight of an entire race on their shoulders. Since their formation earlier in the year they had been the object of derision and ridicule. They had been told by white regiments that they would turn and run at the sound of the first shot, that they would never be brave enough to fight like the white troops. They couldn’t even have one of their own as a leader because they were thought to have no leadership qualities. Now, led by their white colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, they were determined to show their critics how wrong they were.

The 54th Massachusetts was not fighting its first battle. Just two days earlier they had been blooded in action on James Island off South Carolina, in what history would eventually refer to as the Battle of Grimball’s Landing. There, they checked an advance by the Confederates, enabling the 10th Connecticut to safely withdraw after finding themselves in danger of being cut off from the rest of the Union troops. The 54th lost 43 of their men that day, with 14 killed, 17 wounded, and 12 taken captive. Sgt. William Carney had been terrified but had done his duty.

Carney, like many of the men of the 54th, had been born into slavery. When his family attained their freedom, they moved from Virginia to Massachusetts, possibly utilizing the Underground Railroad. When the Emancipation Proclamation was adopted, it opened the door for the recruitment of young black men as soldiers, and William had signed up. Assigned to Company C of the 54th Massachusetts, he was about to become a hero.

The regiment moved through a phalanx of white regiments who awaited their turn to join the assault. Carney and his friends were surprised to hear shouts of encouragement from their white counterparts, many of whom had jeered them just days before. When the 54th got within 150 yards of the fort, the Confederates opened fire, taking a deadly toll. The assault now escalated to a charge on the double-quick.

Climbing the parapet, Col. Gould raised his sword and shouted, “Forward, 54th!” Those were his last words, as he fell with three fatal wounds. Around him, Carney saw other men falling before they could fire a shot. Other Union regiments had fallen in behind the 54th and were meeting a similar fate. Unable to distinguish friend from foe through the gathering smoke from the gunfire, a New York regiment began firing into the Union ranks that had gained the parapet, adding to the carnage.

With his eyes stinging from the perspiration that now dripped into his eyes to mingle with the smoke of battle, Carney lowered his head and advanced, stopping only to reload after each shot. As he fought his way up the sandy wall, he suddenly saw the regimental color bearer fall just feet away, fatally wounded. Carney scrambled to catch the flag before it touched the ground, and holding the colors as high as he could, he continued his advance. When the attack faltered, he planted the staff firmly into the sand, defiantly holding it upright. If he could no longer advance, he could still hold his ground.

As darkness gathered, he continued holding the flag, refusing to relinquish it to soldiers who were dropping back. When the official order to retreat was finally given, other men from the 54th assisted him back to safety, still grasping the flag. During the retreat, he was badly wounded twice but still held the flag high. Before allowing someone else to take the colors so he could receive medical treatment, he proudly proclaimed that the flag had never touched the ground.

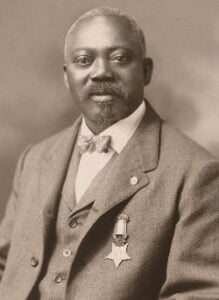

In June 1864, Carney received his discharge due to the lingering effects of his wounds. He returned home, got married, and became a mail carrier for 32 years. On May 23, 1900 he received the Medal of Honor, his citation reading, “When the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back he brought off the flag, under a fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.”

Through no fault of his own, he quickly found himself embroiled in controversy. Credited with being the first Black man to earn the Medal of Honor, others soon also claimed the honor. In truth, more than 20 Black men had received the Medal by the time Carney was awarded his, the first being Robert Blake for his actions on the USS Marblehead on Christmas Day 1863. Blake had received his Medal on April 16, 1864, some 36 years earlier than Carney, despite earning his five months after Carney’s action. Notwithstanding the controversy, the honor of being the first Black man to actually earn a Medal of Honor remains Carney’s.

William Carney died on December 9, 1908 at Boston City Hospital from injuries received in an elevator accident while working at the Massachusetts State House for the Department of State. He was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford, Massachusetts. A replica of his Medal of Honor is engraved on his tombstone.