3 Ways to Live the Value of Commitment

Think about the commitments in your life. What do they all have in common? A promise. Commitment is a pledge to give your time and energy to something or someone…

By Noelle Wiehe, contributor

When Gordon Ray Roberts was a kid in the 1950s, it seemed as if nearly every adult man in his hometown of Lebanon, Ohio, had served in the military. Many had fought in one of the two global wars, plus the Korean War, before coming back to the county seat, its population hovering below 5,000 people. But the whole town would come out for patriotic parades. “Everybody’s father, every business leader, every coach that you had in school, your teachers where you’re learning your history lessons, they’re all veterans,” Roberts, 73, recalled.

He never could’ve guessed that the veterans would someday gather to honor his patriotism, too. But they did in 1971, after he received the Medal of Honor for combat heroism in Vietnam.

On July 11, 1969, during Operation Montgomery Rendezvous in Thừa Thiên Province’s A Sầu Valley southwest of Huế, the rifleman nicknamed “Bird Dog” was fighting to save the lives of his fellow soldiers in the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), the same division his father fought for during World War II. Roberts’ Company B of the 1st Battalion, 506th Infantry was trying to take Hill 996 but got pinned down by a buzz saw of entrenched North Vietnamese troops. Braving machine gun fire and grenades, Spc. 4th Class Roberts stormed a two-man bunker, took it, and then turned toward a second redoubt. When a burst of enemy gunfire slapped his rifle out of his hand, Roberts grabbed another carbine dropped by a comrade and used it to take the bunker. Then he rushed toward a third bunker, destroying it with grenades. Despite being cut off from his platoon, Roberts kept going, assaulting a fourth bunker before helping wounded soldiers to safety and medical evacuation. But 16 fellow soldiers died on Hill 996, including his battalion commander, Lt. Col. Arnold Hayward.

After promoting him to sergeant, the Army credited Roberts with directly “saving the lives of his comrades” and serving “as an inspiration to his fellow soldiers in the defeat of the enemy force,” according to his Medal of Honor citation. Asked today what he recollects about the brutal battle for Hill 996, Roberts said he couldn’t remember details from that far back. “You remember the overall flavor of things, you know? It was a desperate time and you just did what you had to do to get through it,” he said.

But Roberts vividly recalls the frenzied moments leading up to his Medal of Honor ceremony. He was enjoying a weekend pass from Maryland’s Fort Meade to his southern Ohio hometown when a call came from the Pentagon to get back. “I had one brother that was on a ship in the Mediterranean and another brother that was on a ship in the Pacific. They flew both of them and as well as my stepfather, my mom and my sister from there in Ohio,” Roberts said.

Lebanon pitched the parade for him and a fellow soldier shortly after that. “The town was very proud,” Roberts said. “You can see and feel your hometown and the people that you look up to admiring those who served and placing that kind of importance on folks to serve their country when the time comes,” he added.

But Roberts worries about what that sort of celebration would look like today in America. Patriotism is far from dead, but he frets “there’s two sides now” because of a political divide, and too many citizens have come to believe “it’s not my government…One side looks at the other side as completely immoral, and that’s just not the case,” he said.

In the last 25 years, national polls show that patriotism and service face a troubling decline among Americans. According to a 2023 poll by the Wall Street Journal and the National Opinion Research Center, 38% of Americans, including 23% under the age of 30, deem patriotism “very important” to them. In 1998, this sentiment was notably higher at 70%. In that same poll, Americans who valued involvement in their community as “very important” fell to 27% — a staggering decline from the 62% who thought so in 2019.

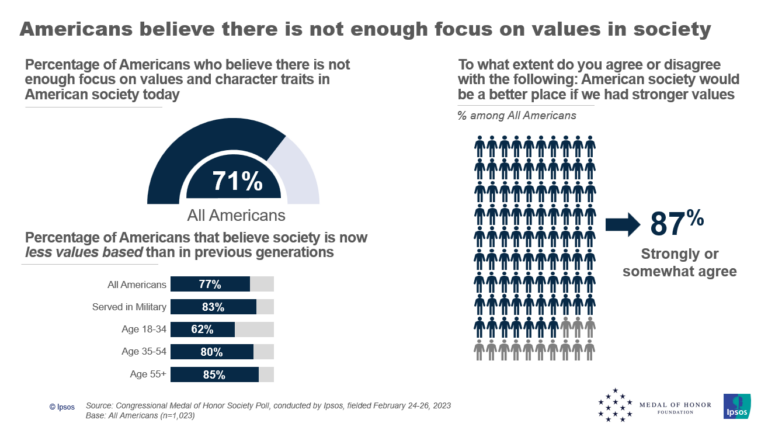

In the 2023 Medal of Honor values poll, conducted by Ipsos 77% of Americans believe that, compared to previous generations, American society is now less values-based. Most agree that role models, like Colonel Roberts, are needed to strengthen character and values in America.

Roberts had joined the Army as a 17-year-old in 1968, shortly after graduating from high school. He left the military in 1971 and earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology from the University of Dayton three years later. He spent nearly two decades as a social worker. He married and helped raise a son and daughter. And then in 1991, he accepted a direct commission and returned to the Army. He percolated up the commissioned ranks, serving in South Korea, Haiti, Kuwait, Iraq, and at several commands in the U.S., including helming the brigade at Walter Reed Army Medical Center between 2008 and 2010. He later served as 1st Sustainment Command’s forward chief of staff at Camp Arifjan in Kuwait before retiring as a colonel in 2012.

That capped a career built on service, the same sort of commitment to his fellow Americans he carried up Hill 996 and through his days as a social worker. Despite their ideological differences, he believes most citizens share those values, too.

Colonel Roberts’ life, in and out of uniform, is a testament to patriotic service. “I still think that the vast majority of people regardless of their political opinions, any moment in time, I still think the majority of people believe this is by far the greatest nation on Earth. And that the best thing about it is that it can always get better,” Roberts said.

*****

Noelle Wiehe is a contributing writer for the Medal of Honor Foundation. She is an Army veteran and career military journalist, her work having appeared in Coffee or Die Magazine, The War Horse, and Military Times. She also serves the military and veteran community through her work for the Defense Health Agency and Military Veterans in Journalism.

*****

To stay up-to-date on upcoming events, special announcements, and partner/Recipient highlights, sign up to receive our monthly newsletter.

About the Congressional Medal of Honor Society

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Medal of Honor, inspiring America to live the values the Medal represents, and supporting Recipients of the Medal as they connect with communities across America.

Chartered by Congress in 1958, its membership consists exclusively of those individuals who have received the Medal of Honor. There are 63 living Recipients.

The Society carries out its mission through outreach, education and preservation programs, including the Medal of Honor Museum, Medal of Honor Outreach Programs, the Medal of Honor Character Development Program, and the Medal of Honor Citizen Honors Awards for Valor and Service. The Society’s programs and operations are funded by donations.

As part of Public Law 106-83, the Medal of the Honor Memorial Act, the Medal of Honor Museum, which is co-located with the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s headquarters on board the U.S.S. Yorktown at Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, was designated as one of three national Medal of Honor sites.

Learn more about the Medal of Honor and the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s initiatives at cmohs.org.