Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

Captain Charles G. Gould was 71 years old when he died December 5, 1916. He survived critical wounds received during the Civil War and received the Medal of Honor in his golden years for a daring and inspiring charge into the Confederate works at Petersburg, Virginia.

The siege of Petersburg, Virginia, was drawing to a close after 292 grueling days. It was April 2, 1865, and the Civil War was winding down. Union troops sensed victory. Under the overall command of Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant, the Union army launched an assault on the fortifications of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which by now was barely hanging on. Their supply lines had been disrupted and the defenses were stretched to the breaking point. Southern forces were now desperately hoping to delay the Union assault long enough for Confederate government officials and the remainder of the Confederate army to retreat from Petersburg and Richmond. By the next day, Union troops occupied both cities, while other Federal forces pursued the Confederates. The pursuers caught and surrounded the Southerners at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, where Lee surrendered on April 9, effectively ending the war.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

Charles Gilbert Gould got a rough start in life. At the age of two, while visiting his grandparents with his family, he was drawn to a boiling pot of applesauce while the adults talked nearby. When he leaned over the pot to draw in the enticing aroma, he lost his balance and tipped the pot over, spilling the contents onto his legs. The applesauce scalded his legs so badly that he would not be able to walk until he was six years old.

When the call went out for volunteers to join the Union army to put down the Southern rebellion, Charlie’s daredevil personality got the better of him. Against his parents’ wishes, he walked 20 miles to the nearest recruiting station. Once there, he was able to convince those in charge that he was old enough to serve and he mustered into the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery. A good soldier, he worked his way up through the ranks, becoming captain of Company H in the 5th Vermont Volunteer Infantry by late 1864.

Now it was April 2, 1865, and the 20-year-old was nervous. Talk around the campfires at night was that the Rebels couldn’t hold out much longer. If that was the case, he reasoned, he didn’t want to get killed this close to the end. He wanted to go home to see his family. But he also knew that he had a duty to perform, and as an officer, he had to set an example for the men under his command.

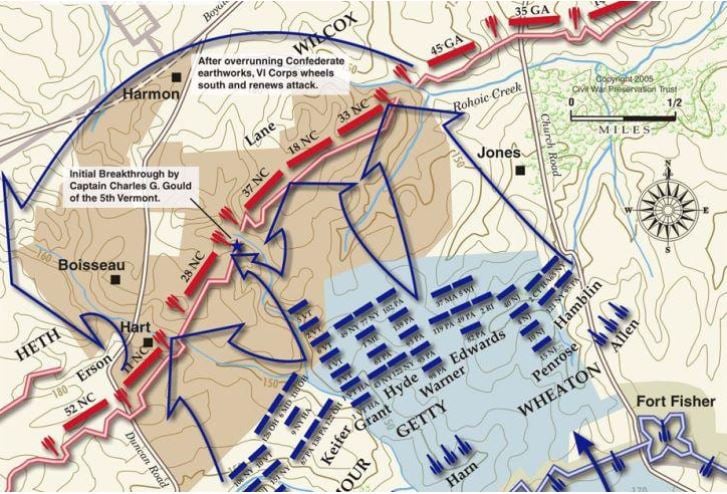

His concerns were not unfounded. The 5th Vermont Infantry had been assigned the task of leading the VI Corps attack along the Boydton Plank Road on the far left flank. Gould led his men across a branch of Arthur’s Swamp until they could see the Confederate wall ahead. When most of the troops veered to the right, taking them off course, an authoritative voice from the rear commanded “Bear to the left,” hoping to redirect the assault. Assuming he had just heard a direct order, he moved to his left. His adjustment placed Company H in an isolated position.

As Gould led the few men who had followed him toward a Confederate battery, he found a small gap in the abatis that had been thrown up by the Rebels. Gould rushed through it, but the limited size of the opening caused a delay by the rest of the company. Unaware that his men were no longer immediately behind him, Gould jumped into a ditch at the base of the Confederate works.

Now under heavy fire, he knew he had to move quickly. Still believing his men had closely followed him, he rushed up the parapet. Brandishing his sword, he met the Confederate line alone, where he was met by ferocious opposition. Several Rebels came at him, swinging clubbed muskets and bayonets. A bayonet was thrust into his mouth, exiting through his cheek. Despite his injury, Gould killed the man who had wounded him. In the hand-to-hand combat that followed, Gould was wounded two more times, once when he was cut on the side of the head after being struck by a saber, the second when stabbed in the shoulder by another bayonet. He was struck by several clubbed muskets until Corporal Henry Recor, who had finally reached the line himself with Company A, grabbed Gould and pulled him back over the works.

Badly wounded, Gould stumbled his way more than a mile back to the rear, where he told commanders that reinforcements were needed immediately. Only after being assured that reinforcements were moving forward did he ask for medical assistance. It wasn’t long before the Confederate line broke, as Federal troops poured over the parapet.

Gould survived his wounds and soon was documented as the first Union soldier to break through the Confederate works. In a letter to his family he downplayed his wounds and noted that his biggest regret was that his wounds prevented him from reaching Richmond. On July 30, 1890, his effort was rewarded when he was presented with the Medal of Honor. Gould died December 5, 1916, but his heroism is still told by a wayside marker at the approximate location of his exploits along Petersburg’s Breakthrough Trail. A painting in the Battlefield Visitor Center at Petersburg depicts the moment he climbed over the top.

Petersburg Breakthrough from American Battlefield Trust on Vimeo.

Sources:

Medal of Honor Citation, CMOHS, https://www.cmohs.org/recipients/charles-g-gould, accessed November 13, 2021

The Common Soldier, Pamplin Historical Park, https://pamplinpark.org/the-common-soldier/, accessed October 26, 2021

Alexander, Edward S., Breakthrough at Petersburg: First Man Over the Works, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2015/04/02/breakthrough-at-petersburg-first-man-over-the-works/, accessed November 15, 2021