Daniel G. George: David vs Goliath on the River

In April 1864 the Confederate navy launched a new ironclad gunboat, christened the Albemarle. The Albemarle, called by her builder “… the most perfect vessel of her size ever constructed…

When the South seceded from the Union it had no seagoing navy. If it had any chance of neutralizing the superiority of the Union’s navy, it would have to devise a strategy that would be unconventional as well as effective. That strategy revolved around commerce raiding. The ship that was most successful at this proved to be the CSS Alabama.

The Alabama, built in England, would ultimately be responsible for destroying 65 Union merchant ships, roughly one of every four merchant ships lost. In the North, insurance rates skyrocketed, shippers encountered a shortage of available ships because owners were reluctant to risk losing them to the Confederate raiders, and when ships became available there was a shortage of crewmen willing to risk their lives at the hands of the raiders. Hundreds of Northern ships naively changed their national registries in hopes of becoming less attractive targets, quickly finding out that that would only be minimally successful.

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, under pressure from Northern merchants, assigned several ships to track down the raiders, specifically the Alabama. One of those ships, the USS Kearsarge, located the Alabama in Cherbourg, France in June 1864.

The ensuing battle resulted in the Alabama being sunk in 200 feet of water. The wreck would not be found until 1988, and in 2002, archeological expeditions were dispatched which brought up more than 300 artifacts, including such treasures as the ship’s bell and guns, one of which was still loaded and ready to fire.

Seventeen Medals of Honor were awarded to Kearsarge crew members for the battle.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

Of the 1,522 Medals of Honor awarded during the Civil War, the recipient who may be the most obscure is Joachim Pease, seaman on the USS Kearsarge. There is no known photograph of him. His birth date is unknown, with determination of the year only approximated by information on his enlistment papers. There is no way to determine his actual date of birth, nor is there any record of his death. And even his birthplace is open to conjecture.

Pease is known to have enlisted at the age of 20 on January 18, 1862. It is this information that provides an estimate of his birth year as 1842. His enlistment rank was Ordinary Seaman and he was described as having black eyes and black hair, a “Negro” complexion, and standing 5’-6” tall. His rank of Ordinary Seaman indicates that he had naval experience from somewhere. Normally African-Americans only held the lowest ranks of Boy, or Landsman. To attain the rank of Ordinary Seaman he would have had to show significant competence, probably from prior experience on the water. Where he acquired that level of ability can only be guessed at due to the unknowns in his personal history.

His birthplace is listed as Togo Island, although his Medal of Honor citation indicates he is from Long Island, New York. Handwriting specialists, however, insist that the T in Togo Island is actually an F, making his birthplace Fogo Island, rather than Togo Island. This narrows it down to one of the two Fogo Islands in the world. One is in Newfoundland, Canada, the other in Cape Verde, Africa. No Newfoundland records show any names similar to Joachim Pease. That would seem to indicate that he was from Cape Verde which, in fact, is actually plausible. Cape Verde was a regular stop for whaling ships to pick up supplies, and it was said that many islanders joined the crews of these ships. While there is no certainty, it is not much of a stretch to assume Pease joined on with one of these ships as a means of coming to the United States. In fact, a ‘Joakim Pease’ is shown in the ship log of the whaling vessel Kensington on her 1857-1861 cruise out of New Bedford, Massachusetts. It is entirely possible that Pease, who would have been 15-19 years old depending on when he joined the cruise, came to this country on board the Kensington. This would be consistent with his 1862 enlistment into the navy and provide a clue as to where he learned enough to be an Ordinary Seaman.

His naval ship, the USS Kearsarge was a Mohican-class sloop of war. Commissioned January 24, 1862, the Kearsarge carried seven guns: two 11” smoothbore pivot guns, four 32-poounder smoothbores, and one 30-pounder howitzer. On February 5, 1862 the Kearsarge left Portsmouth, New Hampshire on her maiden voyage.

Ironically, until her encounter with the Alabama on June 19, 1864 this sloop of war never actively engaged directly with any Confederate ships. She was part of the blockades of the CSS Sumter, the CSS Rappahannock, and the CSS Florida, but never had actively fought. To carry the irony a bit further, the Alabama did have one encounter with a Union ship, the USS Hatteras, but never set into any Southern ports over her entire voyage.

On June 12, 1864, the Kearsarge’s Captain John Winslow learned that the Alabama had put in at Cherbourg, France for repairs to her boiler and copper hull sheeting. Winslow immediately moved toward Cherbourg, arriving June 14. The Alabama’s Captain Raphael Semmes agreed to fight the Kearsarge as soon as he had gathered his crew, which had been granted leave, and restocked his coal supply.

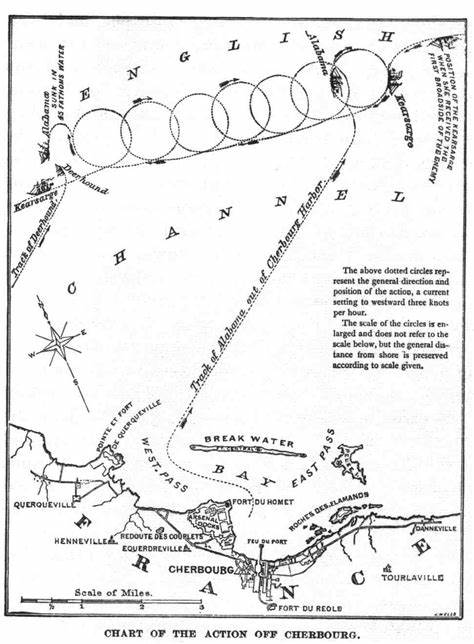

Five days later, on June 19, 1864, the Alabama steamed out of port, closely followed by the French ironclad La Couronne. The La Couronne, whose sole role was to enforce French neutrality, would withdraw once the Alabama reached the three-mile limit.

Just before 11:00 am the Alabama fired first. The Kearsarge, which had draped her extra anchor chain over the sides, effectively making her an ironside, returned fire a few minutes later. The two ships circled each other seven times in the course of the battle, which lasted a bit longer than an hour. The Kearsarge gunners fired fewer times but followed their instructions to aim carefully before firing, ensuring that their shells would be more accurate. Meanwhile, the Alabama’s powder proved faulty, and many of her shells proved ineffective even when they found their mark. The Southern ship’s gunners began alternating shot and shell in an effort to increase their effectiveness, to no avail. One of the shells famously lodged in the Kearsarge’s sternpost but failed to explode.

Pease, serving as the loader on one of the 32-pounder guns, which was located on the forward position of the gundeck, labored at his position as the thick, acrid smoke burned his eyes and made breathing difficult. An Alabama shot passed through the roof of the Kearsarge’s engine house. Another cut through her rigging, sending yardarms askew and threatening to drop them onto the deck. Another shell struck the Kearsarge’s hull, wounding three of the crew. One of them, Ordinary Seaman William Gowin, would suffer for nine agonizing days before succumbing to his wounds, making him the only fatality aboard the Union ship.

The carnage aboard the Alabama was far worse. An 11-inch shell burst through one of her gun ports, wiping out half of the gun crew. First Lieutenant John McIntosh Kell, aghast at the gore, ordered Seaman Michael Mars to fetch a shovel and throw the body parts overboard before resanding the deck to provide better footing. When a shell tore away the spanker gaff, which held the Alabama’s colors, the crew immediately ran another up the mizzenmast in a show of defiance.

However, the accuracy of the Kearsarge’s gunners eventually proved to be too much for the Confederate raider. Her engines rendered useless, the colors were struck and a white flag raised at her stern. As the once proud raider slowly slipped beneath the surface, lifeboats from the Kearsarge began to pick up survivors, assisted by pilot boats from the shore and an English yacht, the Deerhound. The Deerhound, carrying 40 survivors, including a wounded Captain Semmes, slipped away and took the survivors to England. Pease and the rest of his gun crew fired an errant shot in an attempt to stop her, but the yacht successfully escaped, creating a controversy that raged for several months, with Winslow arguing that the survivors were prisoners of war. The English countered by saying that the survivors had technically reached English soil as soon as they boarded the Deerhound and could not be taken as prisoners of war.

Other controversies included the fact that England had illegally served as the construction site for the Alabama and numerous other Confederate raiders. An international tribunal held later in Geneva agreed, and the United States was awarded $15,500,000 in gold.

Casualties on the Kearsarge were limited to the three men wounded, one of them mortally. The Alabama suffered nine men killed or mortally wounded, with 20 more wounded and 19 additional men missing and presumed drowned. The Kearsarge took on an estimated but unconfirmed 64 survivors, with an additional 12 rescued by pilot boats. These were in addition to the 40 picked up by the Deerhound. It would take decades for Union shipping to fully recover from the devastation rendered by the Confederate raiders.

The Kearsarge’s Acting Master David H. Sumner, commander of the 32-pounders, singled out six men in his report for their performances during the battle. One of them was Joachim Pease. Sumner does not specify what Pease actually did. When the Kearsarge returned to Boston on November 7, 1864, Pease routinely went about his duties until his discharge on January 13, 1865. That date is the last that he is heard of. It is believed that he either returned to Cape Verde or signed on with another ship, spending the rest of his life at sea.

On December 30, 1864, General Orders No. 45 announced the awarding of 146 Medals of Honor to men of the Union Army and Navy for various actions. Five of those Medals were awarded to African-Americans. One of those five was Joachim Pease for his non-specific actions in the battle with the Alabama. All told, 17 Medals were awarded to Kearsarge crew members.

Pease never received his medal, probably because he had faded into history and couldn’t be located. It is likely that he never was aware that he had received the honor. His Medal is housed at the Naval Historical Center at the Washington Navy Yard in Washington, DC. His citation reads, “Served as Seaman on board the U.S.S. Kearsarge when she destroyed the alabama [sic] off Cherbourg, France, 19 June 1864. Acting as loader on the No. 2 gun during this bitter engagement, Pease exhibited marked coolness and good conduct and was highly recommended by the divisional officer for gallantry under fire.”

Further reading:

Gindlesperger, James, Fire on the Water, (Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Publishing Co., 2003).

National Archives and Records Administration, Weekly Returns of Enlistments at Naval Rendezvous (Enlistment Rendezvous), Enlistments in New Bedford, Mass. in 1861/Return of the United States Naval Rendezvous, New Bedford, Mass., for the week ending January 18th, 1862″, v. 18, p. 40; Records Group M1953, Washington, D.C.

United States Naval War Records Office, Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (1896), Series II, Vol. 2, pp. 66–67.

Stevens, Danny and Ashton, Jennie, The Search for Joachim Pease, Naval History and Heritage Command, February 18, 2020, https://usnhistory.navylive.dodlive.mil/Recent/Article/2686980/the-search-for-seaman-joachim-pease/, Accessed December 8, 2023.

*****

To stay up-to-date on upcoming events, special announcements, and partner/Recipient highlights, sign up to receive our monthly newsletter.

About the Congressional Medal of Honor Society

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Medal of Honor and its Recipients, inspiring Americans, and supporting the Recipients as they connect with communities across the country.

Chartered by Congress in 1958, its membership consists exclusively of those individuals who have received the Medal of Honor. There are 65 living Recipients.

The Society carries out its mission through outreach, education and preservation programs, including the Medal of Honor Museum, Medal of Honor Outreach Programs, the Medal of Honor Character Development Program, and the Medal of Honor Citizen Honors Awards for Valor and Service. The Society’s programs and operations are funded by donations.

As part of Public Law 106-83, the Medal of the Honor Memorial Act, the Medal of Honor Museum, which is co-located with the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s headquarters on board the U.S.S. Yorktown at Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, was designated as one of three national Medal of Honor sites.

Learn more about the Medal of Honor and the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s initiatives at cmohs.org.