Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

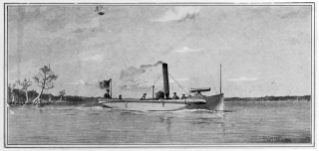

In April 1864 the Confederate navy launched a new ironclad gunboat, christened the Albemarle. The Albemarle, called by her builder “… the most perfect vessel of her size ever constructed …,” was a wooden ship covered with nearly five inches of iron fabricated into eight sloping sides and armed with two 6.4 inch Brooke pivot rifles. One cannon was placed forward, the other aft, and both could fire from three different fixed positions. Each gun was protected on all sides by heavy iron shutters. Two steam engines powered the craft, and the Albemarle quickly made her presence felt on the Roanoke River near Plymouth, North Carolina. There she rammed and sank the USS Southfield and drove off the USS Miami. Assisted by a bombardment from the Albemarle’s rifled cannon, Confederate troops then captured Plymouth and nearby forts, along with 1,600 Union prisoners and 25 pieces of artillery. Throughout the summer of 1864 the Albemarle dominated that section of the river. In an effort to destroy the Albemarle, a plan was approved to use a small 30-foot picket boat fitted with a spar torpedo to approach and sink her.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

Borrowing from William Shakespeare, Theodore Roosevelt is often credited, possibly erroneously, as saying “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.” A man from a small New England town was one of those rare breeds who gain notoriety through a combination of the last two of Teddy’s designations.

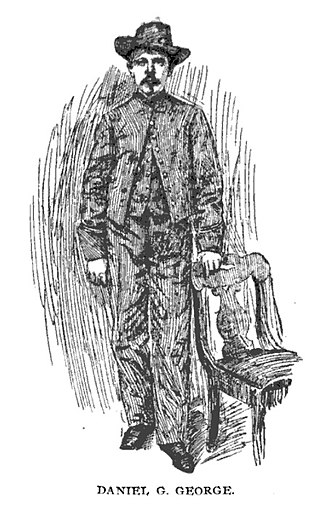

Daniel Griffin George was born in Plaistow, New Hampshire, on July 7, 1840 to Lyman P. and Eliza (Horton) George. Following an uneventful boyhood, he set sail on a whaling ship at age 17, beginning a life of adventure and excitement matched by very few men. As a young sailor, he survived a near sinking when a whale smashed into the side of his ship, held on for dear life when the ship was tossed mercilessly by fierce storms, and cheated death when he was rescued from freezing ocean waters when his whaler was shipwrecked.

After four years at sea, he embarked on a new adventure, enlisting in Company D of the Union army’s 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. He would eventually fight in 21 Civil War engagements, including the Battle of Antietam. On June 17, 1863, his horse was shot and killed, pinning George’s leg, which had been broken in previous fighting at Hilton Head. Unable to move, he was taken prisoner and sent to a Confederate prison camp, then moved successively to Libby Prison, Castle Thunder, and finally to Belle Isle, an island in the middle of the James River near Richmond. At Belle Isle, he talked a guard into helping him escape, and he worked his way back to his regiment.

At the end of his enlistment he reenlisted, soon being promoted to lieutenant. However, the call of the sea was strong, and he spurned his new commission and applied for a transfer to the Union Navy. Assigned to a Receiving Ship at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, he learned that a new sloop of war, the Chicopee, was gathering a crew. When he was turned down for an assignment to the sloop, the crafty George found another seaman, William Smith, who had been assigned to the Chicopee but preferred to remain in his old assignment. George convinced Smith to exchange papers, and when the new crew was assembled, George signed on as William Smith.

Word eventually reached the Chicopee that Lieutenant William B. Cushing would be commanding a small picket boat, fitted with a lanyard-detonated torpedo, on a mission to sink the Confederate ironclad Albemarle, which had been wreaking havoc on the Roanoke River. George immediately volunteered to go with Cushing. The crew believed their mission was suicidal, and for some it would be.

On the night of October 27-28, 1864, Cushing and his 15-man crew, which now included George, began working their way upriver under the cover of darkness. Traveling along the river bank and through the swamps, they slipped past rebel sentries stationed on a schooner placed in the middle of the river. However, as they approached the Albemarle, an on-board sentry detected them and sounded the alarm. Under heavy fire, the picket boat, with George, Cushing, and one other seaman in the bow, sped toward their target, powering through a barrier of floating logs that protected the larger ship. When they got within 30 feet of the Albemarle, Cushing ordered George to lower the torpedo. Waiting anxiously for the torpedo to reach under the Albemarle, George gripped the lanyard which, when pulled, would detonate the explosive.

At Cushing’s command, George pulled the lanyard. The resulting explosion tore a huge hole in the Albemarle’s port bow, causing her to quickly sink into the thick mud on the river bottom. As expected, the explosion also threw Cushing’s entire crew some thirty feet through the air and into the river, killing several. George, however, although injured, was able to swim in the direction of the shore. Weighed down by his heavy pea jacket and his pockets full of ammunition, he found his progress dangerously slow, and when he finally reached shore, he found several Confederate soldiers waiting for him. Captured for a second time, he was taken to Salisbury Prison in North Carolina, where he remained until his release at the end of the war. Upon release, he rejoined the crew of the Chicopee until he mustered out on June 17, 1866.

As a result of the sinking of the Albemarle, the Union fleet regained control of the Roanoke River. The next day the city of Plymouth, North Carolina, was recaptured.

On December 31, 1864, under General Orders No. 45, Daniel George and his crewmates were awarded the Medal of Honor for their actions. His original citation noted that George was also known as William Smith. In recognizing George, a Congressional report stated, “The romance of war has seldom developed a more extraordinary character, and never has exhibited more elevated through unconscious patriotism and sublime courage than Daniel G. George.”

Daniel Griffin George died on February 26, 1916 of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was buried at the Locust Grove Cemetery in Merrimac, Massachusetts.

Sources:

Additional Reading: