Iwo Jima Commemoration: Sergeant Darrell Cole, the Fighting Field Music

During World War II, when U.S. Marines landed on Iwo Jima on February 19, 1945, they found the Japanese forced well-entrenched. It took the Marines 36 days to take the…

Thomas Hudner, Jr., learned early in life that the value of the individual is based neither on wealth nor status, skin color nor family background, but rather on the quality of his character and the beliefs by which he lives. This was a family value that reached back several generations to an Irish immigrant who came to Massachusetts in the 1800s; it was a value that Hudner lived by his entire life.

By: Kris Cotariu Harper, EdD

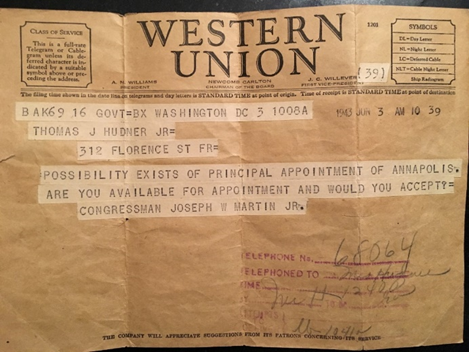

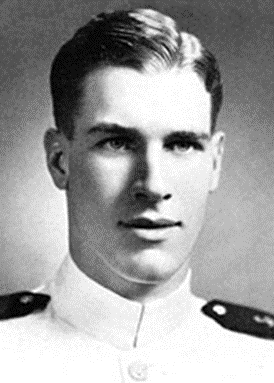

Thomas Hudner, Jr., was born in Fall River, Mass., in 1924, the oldest of five children. Following a family tradition, he attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass., where he was captain of the high school track team as well as a member of the football and lacrosse teams. In addition to his athletics, Hudner was a class officer and served on the student council. In the spring of 1943, he was again set to follow his father’s footsteps, this time to Harvard University, when a telegram from Congressman Joseph Martin arrived on June 3, 1943. Thomas Hudner was being offered an appointment to the United States Naval Academy (USNA). Hudner’s decision to accept this appointment was a dramatic change in his life’s direction.

Less than a month after receiving the telegram, Hudner entered USNA as a member of the Class of 1947, which was accelerated due to the ongoing war, and the entire class graduated in June 1946.

The Class of 1947 shaped numerous military and government leaders of the following decades, including the 39th President of the United States, Jimmy Carter, and two Medal of Honor recipients: Thomas Hudner, Jr., for his actions during the Korean War, and James Stockdale, for his actions as a prisoner of war in Vietnam. Hudner and Stockdale remained more than just classmates but established bonds of friendship that lasted throughout their lives and often exchanged visits between families. While not close friends, the Hudners and the Carters visited intermittently over the years and when President and Mrs. Carter were in Boston, they invited the Hudners to their hotel suite.

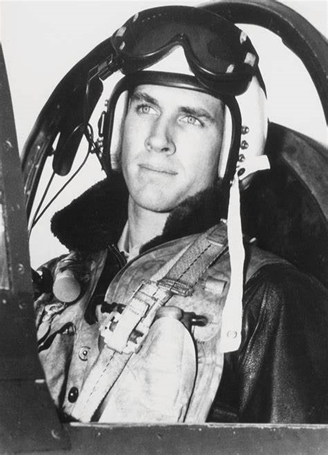

Upon graduation from the USNA, Hudner was assigned to the surface fleet, serving on the USS Helena and then at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. During this time, he developed an interest in aviation and in 1948 was assigned to flight training at Quonset Point, Rhode Island. Early in his training period, he met Ensign Jesse Brown, the first Black American to become a U.S. naval aviator. Brown, the son of a Mississippi sharecropper, had faced severe discrimination in life, as well as in the Navy, and when he first met Hudner he was reticent to extend his hand for a shake. Tom Hudner, however, strode across the room with his hand outstretched and, with this action, began a friendship that bonded these two families for more than seven decades.

Hudner’s son related an incident from December 1949 during his father’s training period while Brown was in the lead and Hudner was following. Hudner realized they were off course and as he was deciding what to do, Brown dipped his wing to signal his wife, Daisy, who was standing in her front yard with their daughter, Pamela, waving at the two airplanes; Jesse had diverted course to fly over his home. One imagines Hudner waved back as the two airplanes banked and returned to base.

Hudner and Brown, both flying F4U Corsairs, were assigned to the USS Leyte which was ordered to the Pacific shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War.

On Brown’s 20th combat mission, December 4, 1950, both men were in a six-plane squadron providing support to the embattled Marines at Chosin Reservoir, Korea. Fifteen miles behind enemy lines, Brown’s aircraft was shot down. The five remaining pilots circled the crash site with little hope that he had survived; to their surprise, Brown had opened his canopy and was struggling to exit the plane, but to no avail. Without much thought, Hudner radioed the others, “I’m going in” (Hudner III, 2021) and made a wheels-up landing, skidding along the snow and ice until he finally came to a stop. Once on the ground, Hudner found Brown slipping in and out of consciousness, pinned inside the airplane with no way of extracting him. When the rescue helicopter arrived, both men considered severing Brown’s leg in order to remove him, but even that procedure was not feasible. Eventually, Brown succumbed to his injuries and Hudner and the helicopter pilot were forced to leave him there.

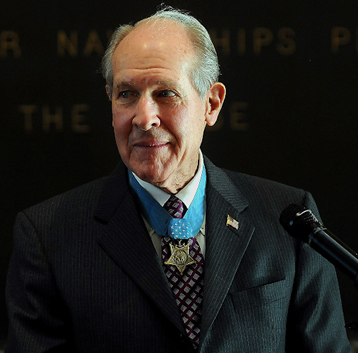

Four months later, Brown’s widow was present when Hudner was awarded the first Medal of Honor for the Korean war for this heroic attempt to save his wingman’s life. Finding a few minutes to speak after the ceremony, Hudner told Daisy that he was with Jesse when he died and the last words he spoke were “tell Daisy I love her” (Hudner III, 2021).

In 1968, Hudner married Georgea Smith, widow of a Navy aviator with three small children, and in 1972 their only child, Thomas Jerome Hudner III, was born.

Thomas Hudner served a total of 27 years in the Navy, completing 27 combat missions in Korea. During the Vietnam War he served as executive officer on the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk. In 1973, he dedicated the USS Jesse Brown at her commissioning, and retiring from the Navy as a captain not long afterwards. In retirement, he relocated to Concord, Mass., where he worked for some time as a management consultant before becoming the Commissioner of Veterans Affairs for the State of Massachusetts.

While everyone recognized Thomas Hudner as a hero, he remained gracious in their attentions and humble in his actions. He often said he did not do anything anyone else would not have done and nothing that Jesse Brown would not have done for him. At one point during his career, Hudner’s hometown of Fall River, Mass., raised several thousand dollars to present as a gift in recognition of his heroism. Hudner gratefully accepted the check and immediately endorsed it to Brown’s widow; she used the money to pay her college tuition.

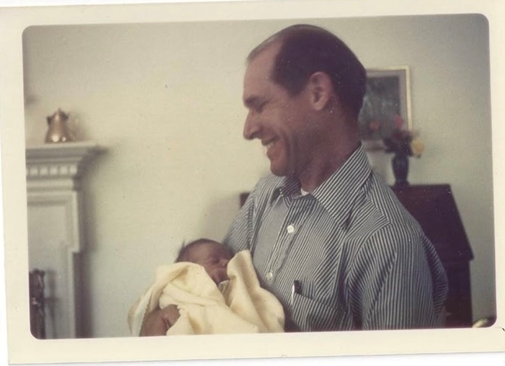

Hudner was known to be an exceptional father and, according to his son never missed an opportunity to support his children in their sports and other activities. Two incidents from Tom III’s childhood tell the story of his father’s creative parenting. While home alone with his baby son, Hudner rigged a bottle so it suspended above the crib and he wouldn’t have to feed the baby. His son explained that he just had to “stretch his neck like a gerbil” and could feed himself. When Young Tom was about eight years old, he and a friend crashed their remote control airplane into a tree, destroying it. Hudner took the model airplane and reassembled and glued the toy back together in perfect proportions. The young friend exclaimed “your dad is ingenious!” (Hudner III, 2021).

In 2013, Thomas Hudner returned to North Korea in an attempt to retrieve Brown’s remains. As with his previous effort to save Jesse, however, he was unsuccessful. He remained a loyal friend to Brown’s widow and her family, making numerous trips to Mississippi to visit over the years, and the Brown family came to Massachusetts in 2015 for the unveiling of Hudner’s portrait that would eventually hang on the USS Thomas Hudner, and again for the commissioning of the ship in 2017.

Thomas Hudner passed away in November 2017 and is interred in Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. Jesse Brown’s family was there to offer their respects. Hudner’s official biography, Devotion: an Epic Story of Heroism, Brotherhood, and Sacrifice, written by Adam Makos, was released in 2016 and is being adapted into a movie; it is currently in post-production and should be in theaters soon.

Reference: Personal interview with Thomas J. Hudner III, 24 November 2021.

*****

Kris Cotariu Harper, EdD, is an Army wife and the daughter of two WWII Navy Veterans. She is an educator and trainer who often writes and speaks on values demonstrated by Medal of Honor recipients.