Capturing a General: Sgt. Everett W. Anderson

As Civil War battles go, the skirmish at Cosby Creek in eastern Tennessee barely merits discussion in any history book. Even serious Civil War scholars will have a difficult time…

You won’t find it on a map, nor will a Google search produce much information. It is only a blip on a list of battles and skirmishes that occurred in Virginia during the Civil War. Yet a skirmish at Newby’s Crossroads produced two Medals of Honor recipients. Named for a freedman named Dangerfield Newby, who made his home there, Newby’s Crossroads rarely even appears on a map of Virginia. It is best found as the intersection of State Routes 618 (Laurel Mills Road) and 729 (Richmond Road) in an unincorporated area of Rappahannock County, Virginia. Even the fighting is usually referred to as having taken place at Battle Mountain, eschewing the name of Newby’s Crossroads altogether.

Dangerfield Newby himself is found in more history books than is Newby’s Crossroads. Newby, who had unsuccessfully attempted to purchase the freedom of his enslaved family, joined John Brown’s raiders in hopes that Brown’s 1859 attack on Harpers Ferry would free his wife and children. As we know, Brown’s attack failed, and Newby became the first of the raiders to be killed in the attack.

In July 1863, the Union army attempted to seal off the passes and gaps in the Blue Ridge Mountains, hoping to trap Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the Shenandoah Valley. However, the Northerners were defeated and Lee’s troops poured through Chester Gap and into Rappahannock County, on their way to Culpepper Courthouse. Standing in their way was Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer with his 1,200 cavalry, accompanied by Company M of the 2nd U.S., Artillery. Vastly outnumbered, Custer’s men were routed. The next day, July 24, 1863, Custer moved his troops to Newby’s Crossroads, where he would once again intercept Lee.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

Early in the morning of July 24, 1863, Horse Battery M of the 2nd U.S. Artillery was among Custer’s troops that struck the flank of Lee’s army. After a brief skirmish, Custer was forced to withdraw. The rear guard consisted of portions of the 5th and 6th Michigan Cavalries and two guns of Horse Battery M of the 2nd U.S. Artillery.

Confederate General Henry L. Benning’s Brigade, hoping to cut off the Union forces, set up an ambush of Custer’s rear guard. As the 6th Michigan approached, Benning’s troops fired a volley that caused the Michigan troops to turn and rush back toward the rest of the rear guard. Reaching the 2nd U.S. Artillery’s Battery M, Colonel George Gray of the 6th Michigan cavalry ordered the battery’s 1st Lieutenant Carle A. Woodruff to cut the horses’ traces, abandon his guns, and follow him. Woodruff, refused, saying “I will never leave my guns!”

Instead, Woodruff unlimbered one of his two his guns and fired with canister rounds. As the guns bellowed, Captain Smith H. Hastings of the 5th Michigan Cavalry arrived and asked what Woodruff wanted him to do to assist. Woodruff answered that Hastings should dismount some of his men and support the battery. As Hastings began to organize his troops, another officer rushed to Woodruff’s side and repeated Colonel Gray’s orders to abandon the guns.

Woodruff refused once again, and shouting to his men that the order had been given to abandon their guns. To a man they all shouted their own refusals, with many crying out that they would all go to Richmond together.

Woodruff ordered his crew to continue firing as he moved his second gun into position with the aid of the Hastings and the dismounted Michigan cavalry. When the second gun was ready, Woodruff’s men fired while Hastings moved his men and 10 horses to the first gun, which they moved to the left of the second gun. When the first gun was in position, Woodruff ordered it to be fired while Hastings repeated his earlier move of the second gun. Each time, when a gun was fired, Hastings moved the other to the left until the two guns were flanking the Southerners. After two hours of fighting, the Rebels withdrew.

Woodruff immediately went to General Custer and reported that the guns were all safe and still in the Union’s possession. At that time, Custer told Woodruff that he knew that runners had been sent to tell him to abandon the guns and the runners had returned and reported that there were many more Southern troops than they realized and they encircled Custer’s men.

Hastings later described the action in an identical manner, adding that Custer was very pleased because, by disobeying orders, Custer’s record of never permitting the enemy to capture a single piece of artillery remained intact.

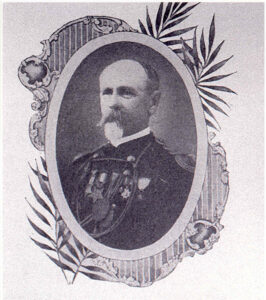

On September 1, 1893, Woodruff’s exploits were recognized with the presentation of the Medal of Honor. His citation read: “While in command of a section of a battery constituting a portion of the rear guard of a division then retiring before the advance of a corps of Infantry, Woodruff was attacked by the enemy and ordered to abandon his guns. Lt. Woodruff disregarded the orders received and aided in repelling the attack and saving the guns.”

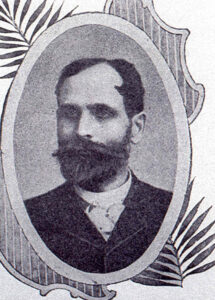

Hastings was similarly honored four years later when, on August 2, 1897, he also received the Medal of Honor for his part in the fight at Newby’s Crossroads. His citation reflected the role he had played that day: “While in command of a squadron in rear guard of a cavalry division, then retiring before the advance of a corps of infantry, was attacked by the enemy and, orders having been given to abandon the guns of a section of field artillery with the rear guard that were in imminent danger of capture, he disregarded the orders received and aided in repelling the attack and saving the guns.”

If you would like to support the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s mission to preserve the legacy of the Medal of Honor and its Recipients, please consider donating to our foundation here.