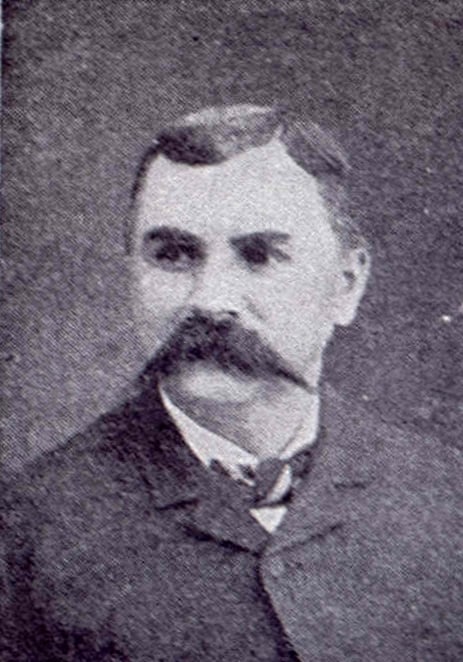

Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

Early in the morning of March 19, 1865, a small detachment of 90 foragers, under the command of Union Captain Charles Belknap, pushed their way through a swamp near Bentonville, in Johnston County, North Carolina. Chasing back a small contingent of Confederate pickets, the Federals proceeded over a small hill only to encounter what seemed to be the entire Confederate army.

Nearby, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman had no idea Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s Southern troops were so close. Hearing the rattle of muskets as Belknap’s troops fought their way out of Johnston’s trap, Sherman still believed that Belknap had encountered only a small band of cavalry. After all, the Confederates, now in the last days of their existence, had only offered token resistance since earlier fighting at Atlanta.

Today would be different, however. Johnston was about to throw up fierce resistance, with fighting that would last for three days. By the time the fighting was over, more than 1,500 of Sherman’s men would be casualties of the Battle of Bentonville. Johnston’s casualties numbered more than 2,600.

This battle would prove to be the last battle between Sherman and Johnston, two bitter rivals. A few weeks later, Johnston would surrender his army to Sherman at Bennett Place, near Durham, North Carolina. On April 9, 1865 General Robert E. Lee would do the same when he surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, Virginia. America’s Civil War was over.

Four Medals of Honor were awarded as a result of the action at Bentonville. Private Peter T. Anderson was one of them.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

Peter T. Anderson was born September 4, 1847 in Darlington, Lafayette County, Wisconsin to Arne and Martha Guliksdatter Kindem Anderson, the second of six children. His early years were, as are most of ours are, unremarkable. Then, Fort Sumter was fired on and the Civil War began. Young Peter was only 14 at the time, and in typical youthful fashion, envisioned himself joining the army and defeating the Rebels single handed. While his family indulged his fantasy, Peter became very restless, and finally, on September 8, 1863, he walked to Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin and enlisted into Company B of the 31st Wisconsin Infantry. He was four days past his 16th birthday.

On the afternoon of March 19, 1865, the would-be conqueror of the entire Confederate army arrived at the Cole Plantation in Bentonville with the rest of the 31st Wisconsin Infantry. The regiment had been ordered to fill a gap in the Union line in support of Lieutenant Samuel Webb’s 19th Battery, Indiana Light Artillery. Anderson had not been feeling well but had ignored orders to get into an ambulance to the rear.

The regiment had just begun to set up breastworks when advancing Confederates charged across an open field, practically surrounding the Wisconsin troops. The 31st Wisconsin, along with eight other Union regiments positioned along the Goldsboro Road were ordered to immediately retreat to avoid being cut off and, in all likelihood, captured. Webb ordered his four 12-pounder Napoleons to limber up and move back with the retreating forces. However, the gunners were only able to get one cannon ready to be removed before Webb was mortally wounded. When Webb fell, his men fled on foot to avoid capture.

As Anderson retreated with his companions, he heard a desperate cry for someone to “… bring out that battery!” When Anderson asked another man from his regiment to assist him, the man refused to go back into the hail of gunfire. Recognizing the need to save the gun, Anderson immediately raced to it alone. Reaching the battery he found that it was already limbered with the horses hitched, ready to be moved.

Turning the horses, he used his ramrod as a whip and began moving the team in the direction of the retreat. To speed things up he attempted to mount the lead horse, only to find that the stirrup had been shot off. Holding on to the horse’s halter, he raced alongside as the Confederates drew closer. Witnesses estimated that Anderson ran with the team about a half mile before he caught up with the retreat.

At one point before he reached the Union troops, several Southerners caught up with him and ordered him to surrender. As Anderson tried to reload as he ran, a minie ball struck the barrel of his gun, bending it and tearing through his right forefinger. Anderson fired his weapon anyway, sending the ramrod into the group of Rebels. As an officer leveled his pistol at Anderson’s head, a shot from an unknown Federal soldier tore into the officer, killing him instantly and enabling Anderson to get away in the ensuing confusion.

Finally reaching the rear of the retreat, Anderson transferred the rescued field piece to the chief of artillery, then nonchalantly went to get another gun as if it had all been a routine task.

That night at bivouac, a messenger arrived at the 31st Wisconsin’s camp and ordered Anderson to report to General William Sherman’s headquarters. Anderson noted in his memoirs that he went to the general’s tent in trepidation, concerned that the general had called for him specifically. As he went, he tried to think of something that he may have done that could bring punishment, but could come up with nothing. Reaching the general’s headquarters, he was surprised when Sherman stood and offered his chair to Anderson. The bewildered private followed his instructions, not realizing how bizarre the situation had become.

Things grew even more surreal when Sherman began praising Anderson and telling him how proud he was of him. Anderson sheepishly listened, first relieved that he was not going to face punishment, then becoming more elated when he was dismissed with the comment, “Your services will be rewarded soon in a more substantial manner.”

Anderson was so taken aback that he failed to clarify what services Sherman was referring to. Just three days earlier Anderson had led an assault after the officers were all scattered in an ambush by the Rebels. Anderson had taken it on himself to rush toward his assailants, with the regiment following. Before the Confederates could reload, Anderson and his companions had taken 75 of them captive. Returning to the line, he found that Sherman had witnessed the entire attack. Was this the service that Sherman had referred to in their conversation, or was it the rescue of the gun belonging to the 19th Indiana, or was it something else?

Anderson got his answer three months later when he learned that he had been awarded the Medal of Honor for his efforts in retrieving the 12 pounder. On June 15, 1865, he received his Medal, along with a captain’s commission and the following citation: Entirely unassisted, brought from the field an abandoned piece of artillery and saved the gun from falling into the hands of the enemy.

Anderson lived another 42 years, marrying Ella M. Kerns in 1867. The two had a daughter, Martha Alice, who was only one year old when her 24-year-old mother died in 1869. Martha Alice, on the other hand, lived to be 102. Anderson remarried in 1885 to Sophia Jensen, and the two also had a daughter together. Named Leone, that daughter lived to the age of 104.

Anderson himself lived until July 26, 1907. He was given a hero’s burial in Newell Cemetery in Newell, Iowa.

Further Reading:

*****

To stay up-to-date on upcoming events, special announcements, and partner/Recipient highlights, sign up to receive our monthly newsletter.

About the Congressional Medal of Honor Society

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, is dedicated to preserving the legacy of the Medal of Honor, inspiring America to live the values the Medal represents, and supporting Recipients of the Medal as they connect with communities across America.

Chartered by Congress in 1958, its membership consists exclusively of those individuals who have received the Medal of Honor. There are fewer than 70 living Recipients.

The Society carries out its mission through outreach, education and preservation programs, including the Medal of Honor Museum, Medal of Honor Outreach Programs, the Medal of Honor Character Development Program, and the Medal of Honor Citizen Honors Awards for Valor and Service. The Society’s programs and operations are funded by donations.

As part of Public Law 106-83, the Medal of the Honor Memorial Act, the Medal of Honor Museum, which is co-located with the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s headquarters on board the U.S.S. Yorktown at Patriots Point Naval & Maritime Museum in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, was designated as one of three national Medal of Honor sites.

Learn more about the Medal of Honor and the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s initiatives at cmohs.org.