Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

On the second day of fighting at Gettysburg, July 2, 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank. Commanded by Lieutenant General James Longstreet, ferocious fighting erupted at Devil’s Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, and Cemetery Ridge. Union Second Corps Major General Winfield Scott Hancock moved reinforcements quickly into position as a countermove.

A key element of the day saw Third Corps Major General Daniel Sickles moving his troops to a forward position in the Peach Orchard, leaving a gap in the Union line. The controversial move is debated to this day as to whether or not the move was a good one. In the ensuing fighting, his Third Corps was decimated and his leg was wounded so badly that it required amputation. Sickles would ultimately receive the Medal of Honor for his action.

At the end of the day, nothing had been settled. That night, Union Major General George Meade called several of his generals to his headquarters at the Widow Leister’s farm on the back side of Cemetery Ridge. There he held a council of war, with the generals agreeing that, of all their options, the best course of action would be to stand solid and fight again the next day. That decision set the stage for the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge by the Confederate army, which would become known to history as Pickett’s Charge.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

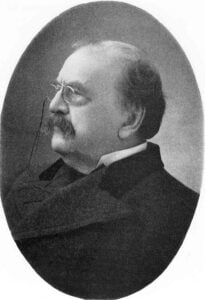

One of the great characters of the Civil war, General Daniel Sickles, left a trail of unpaid bills, broken romances, and political scandals everywhere he went. Born in New York City, he attended the University of the City of New York, today’s New York University. He studied law in the office of Benjamin Butler and was admitted to the bar in 1846. He opened his own law practice and joined the infamous political machine that controlled New York City’s political scene, Tammany Hall.

Over the next several years he served as corporate counsel for New York City, secretary of the United States legation in London, and as a member of the New York State Senate. Along the way, he was instrumental in obtaining the land that would become New York’s Central Park and received a commission in the 12th New York Militia.

In 1852, at the age of 32, he married his pregnant girlfriend, 15-year old Teresa Bagioli, the daughter of a close friend. Both would have several paramours, leading to what could only be described as a rocky marriage.

Three years later, he was elected to the New York State Senate, and to the United States House of Representatives in 1856 and 1858. Although he was only in the state senate for a year, Sickles had sufficient time to be censured by the New York State Assembly for bringing a prostitute onto the Senate floor. He later took the same prostitute with him on a trip to England, where he presented her to Queen Victoria under the surname of a political opponent.

He would gain a new level of infamy in 1859 when a friend tipped him off anonymously that his wife was having an affair with Philip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key, composer of our national anthem. The younger Key was actually a family friend who escorted Teresa to various Washington, D.C., functions when Sickles was not available. If Sickles really didn’t know about the affair, he may have been one of the few people in Washington who didn’t. Claiming to be grief stricken over Teresa’s dalliance with Key, he insisted she confess to the deed in writing. When she did, she refused to use her married name as her signature, using her maiden name instead.

It was only a few days later that Sickles spied Key outside Sickles’s home. Grabbing a gun, he ran outside and chased Key to Lafayette Park, across the street from the White House. Sickles’s first shot struck Key in the groin. It has never been established if that was intentional or just a coincidence, but it was not fatal. As Key begged for his life, Sickles shot a second time, this time striking him in the chest and killing him. Sickles then walked to the nearby attorney general’s office and turned himself in.

Sickles hired Edwin Stanton, who would eventually become President Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of war, as his attorney. When the case came to trial, Sickles played the role of the deceived spouse, saying he couldn’t understand how his wife could betray him in such a way. Conveniently ignoring his own illicit relationships, he said he had forgiven her. He then pled temporary insanity, a rare plea that had been used before in American courtrooms, but always unsuccessfully.

Stanton portrayed Sickles as the real victim in the case, emphasizing how a family friend had seduced his wife. He told the jury that Sickles was a good man, but that he had been out of his mind with grief when he learned that his wife had not been faithful. His arguments were convincing, and a verdict of not guilty was rendered, marking the first time temporary insanity was a successful plea in America.

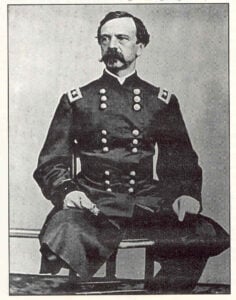

When the Civil War broke out, Sickles saw his opportunity to salvage his honor. He knew that war heroes were held in the highest esteem, and he convinced New York’s Governor Edwin Morgan to allow him to raise a company of volunteer troops. Once that was done, he sought and received approval to organize an entire brigade. The result was the 70th, 71st, 72nd, 73rd, and 74th New York Infantries, which would collectively become known as the Excelsior Brigade. Drawing on his political connections and his prior militia experience, he became colonel of the 70th New York. In September 1861 he was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers, once again a political appointment.

Unable or unwilling to change his character, he gained as many political enemies as he did political friends, and he was forced to relinquish his command in March 1862 when the U.S. Congress refused to confirm his commission. Once again calling in political favors, he reclaimed his rank two months later when the Senate confirmed him by a 19-18 vote.

On January 16, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln nominated Sickles for promotion to major general. The promotion was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on March 9, followed by the official appointment by the president two days later. The timing wasn’t important to Sickles, however. He had already been given command of the Third Corps by his good friend and fellow womanizer, Major General Joseph Hooker, in February. The appointment was keeping with Sickles’s controversial nature, as the appointment made him the only corps commander without a U.S. Military Academy education.

At Gettysburg he was ordered by Major General George Meade to have his corps take a defensive position on July 2, 1863 along the southern portion of Cemetery Ridge, anchoring his northern end to the Second Corps and his southern end at Little Round Top. Once there, Sickles saw the Peach Orchard in his front and, believing its slightly higher elevation gave him an advantage, he moved his men without orders to that location. This stretched his corps too thin and created a salient that the Confederates were able to exploit. It also infuriated Meade, who rushed to speak with Sickles but got there too late. With the Confederates already attacking as part of Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s assault, there was no time to reposition the Third Corps.

Longstreet’s troops routed the Third Corps, decimating it. In the attack, Sickles was wounded in the leg by a cannonball at the Peter Trostle farm. A monument stands today at the site of his wounding. Hiding the pain of his mangled limb as he was being carried off the field on a stretcher, he famously drew himself up on one elbow and made a show of casually puffing on a cigar to rally his men. The leg was later amputated, and Sickles had the amputated limb sent in a coffin-shaped box to the Army Medical Museum (now the National Museum of Health and Medicine) in Washington, D.C. For a time, the bones were used as a teaching aid about battlefield trauma, and Sickles often visited the exhibit of his shattered bones. The display has since been upgraded, with the bones and a cannonball similar to one that caused his wound placed together in an exhibit case.

Sickles remained in the army until the war’s end, receiving appointments as brevet brigadier general and major general. He spent years after the war attacking Meade’s character and defending his decision to move to the Peach Orchard. He also wrote numerous anonymous newspaper articles that declared him the reason the Union won the battle at Gettysburg. Historians still debate the pros and cons of his move.

To his credit, however, he was active in Reconstruction and vigorously pursued fair treatment for freed slaves. He received an appointment as colonel of the 42nd United States Infantry (Veteran Reserve Corps) and retired as a major general. Over the next several years he served as U. S. Minister to Spain (where in typical Sickles fashion he had an alleged affair with Queen Isabella II), chairman of the New York State Civil Service Commission, Sheriff of New York County, and on the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Commission, among other positions.

As chairman of the New York State Monument Commission, he obtained funding for the Excelsior Brigade monument on the Gettysburg Battlefield. The monument was to have a bust of Sickles in its center. However, that never materialized because there was insufficient money left when time came to commission the bust. The reason for the cash shortage? An audit revealed that some $28,000 had been embezzled from the fund, and all indications were that Sickles was responsible, although it was never proven.

In 1892, he was elected to Congress once again, serving from 1893 to 1895, and was instrumental in the development of Gettysburg National Military Park. When asked why he never had a statue to himself at Gettysburg, he would ignore the cash shortage for the Excelsior Brigade monument bust and proclaim that the entire battlefield was his monument.

On October 30, 1897, Sickles was awarded the Medal of Honor for “… most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.”

Sickles died of a cerebral hemorrhage on May 3, 1914, at the age of 94 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, VA.

Further Reading: