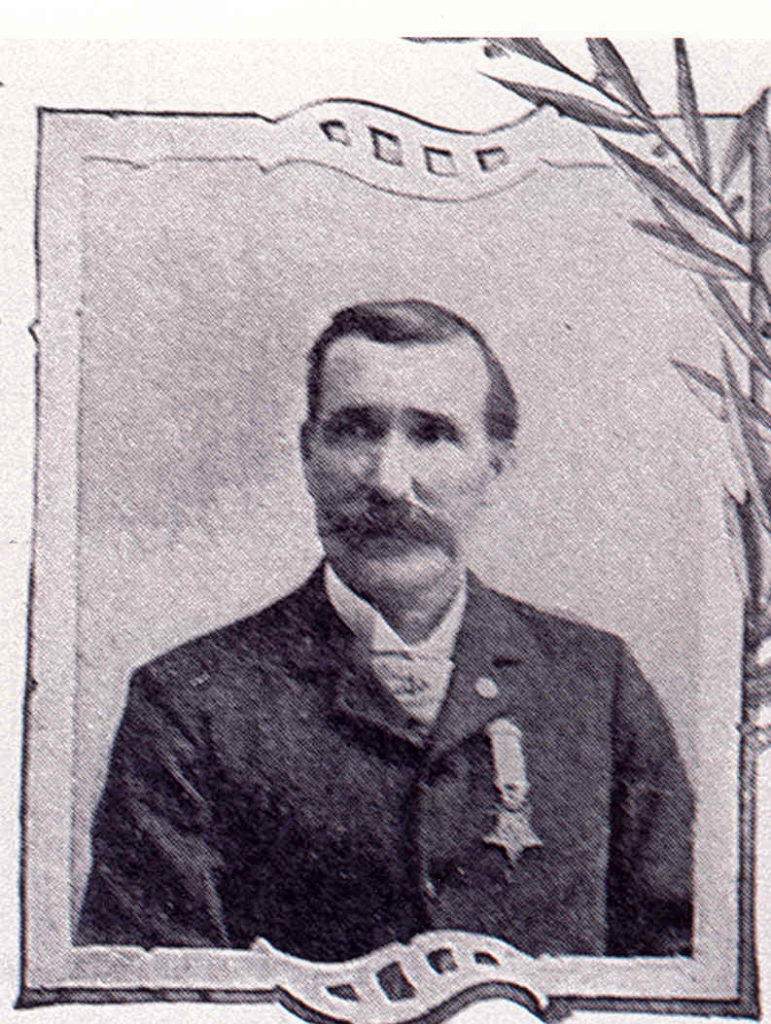

Capturing a General: Sgt. Everett W. Anderson

As Civil War battles go, the skirmish at Cosby Creek in eastern Tennessee barely merits discussion in any history book. Even serious Civil War scholars will have a difficult time…

The Civil War was winding down. Lieutenant General Ulysses Grant was winning the battle of attrition, having stretched Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s depleted army nearly to its breaking point. The Union army now surrounded Petersburg, and Grant was waiting for an improvement in the rainy weather conditions before making his next move. Lee took advantage of Grant’s delay by launching a furious attack that enabled him to gain temporary control of a part of the battlefield known as White Oak Road in Virginia. A counterattack by the Union drove the Confederates back and regained control of White Oak Road for Grant. The fighting around White Oak Road would contribute to sealing Lee’s fate at a larger battle at Five Forks, some five miles to the west. A victory at Five Forks enabled Grant to control the South Side Railroad, a critical supply line and evacuation route for Lee. Lee would surrender his army to Grant at Appomattox just eight days later.

Throughout the Civil War five pairs of brothers received the Medal of Honor. One set of those brothers, James and Allen Thompson, earned their medals at White Oak Road.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

On March 31, 1865, the 4th New York Heavy Artillery (NYHA) was fighting as infantry as part of the famed Irish Brigade under General Nelson A. Miles. Pursuing the enemy, the 4th NYHA arrived at White Oak Road. The war-weary New Yorkers vowed to do everything in their power to end the war, and now the Confederate works were in plain sight a short distance in front of them. Surprisingly, though, not a rebel was in sight. The expected resistance had not appeared.

But Miles was concerned. The silence, broken only occasionally by the crows flying overhead, did not seem natural. Ordering his men to conceal themselves as best they could, he and his aides studied the ground ahead. Fearing that his men were being drawn into a trap, he called for a scouting party of volunteers to advance and evaluate the situation. Seven men stepped forward, including the Thompson brothers.

Miles personally directed them to advance with rifles ready, moving 50 feet apart. The seven were ordered to fire their weapons immediately if they observed any Confederates concealed in the thick underbrush. Pointing out a large oak tree in their front, Miles ordered the group to send a man up the tree and wave his cap if all was well. That would be the signal that it was safe for the brigade to advance.

The seven started out with Allen Thompson in the lead, followed by his brother James. The line stretched out on either side of them. Proceeding slowly through the dense thickets, each man felt alone, unable to see the man on either side. By the time they had advanced about a quarter of the way to the rebel breastworks, they had all drifted toward the center, perhaps unconsciously seeking the reassurance that friendly comrades were near. Gathering amidst the slashings, they whispered anxiously, planning their next move. Unfortunately, that decision was made for them as a contingent of nearly 50 men in gray uniforms rose as one just a short distance to their left, the leader ordering the group to throw down their weapons and surrender.

The seven quickly discussed what to do, recognizing that surrendering meant no signal would be given and the brigade would eventually advance into the teeth of the Confederate army, positioned just behind the outpost. They decided to fight, knowing they had little chance to survive but realizing the volley would serve as a signal to Miles that the enemy had indeed set up an ambush.

Coordinating their movement, the seven fired simultaneously at the Confederates, who answered with a blast of their own. Five of the seven Yankees were killed immediately, but amazingly the two who survived were the Thompson brothers. James Thompson lay badly wounded, while Allen had several holes through his clothes but was unharmed. Allen retreated, rushing back toward the brigade. He didn’t go far before he met them as they advanced toward the gunfire.

As James lay helplessly among his dead comrades, the fighting raged fiercely around him. The Thompson brothers’ brigade took and held the position around the first encounter, while other Federals pushed forward, taking many prisoners and forcing the rest of the Confederates to evacuate their works. As the fighting subsided, a small contingent from the 4th New York Heavy Artillery arrived to bury their dead. Among the five bodies they found James, still alive. He later would say that he had prayed for a ball to end his misery as the ground was being torn up around him with fire from both sides.

Allen Thompson survived the war and lived a full life, passing away on February 27, 1906 at age 58. James, despite his severe wounds, also survived and went on to live another 56 years, when he died on May 23, 1921

On April 22, 1895 brothers James and Allen Thompson were awarded the Medal of Honor, erroneously listing the date of their action as April 1, 1865. Their identical citations read: Made a hazardous reconnaissance through timber and slashings, preceding the Union line of battle, signaling the troops, and leading them through the obstructions.

The brothers became the first pair of siblings to earn the Medal in the same action. When they fought at White Oak Road, Allen was 17 years old and James was 15, placing the two among the youngest recipients of the Medal of Honor in our history.