Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

In early August 1861, Confederate troops under the command of Brigadier General Ben McCulloch, augmented by forces from the Missouri State Guard, wended their way through southwestern Missouri toward Springfield. There, Federal troops under Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon waited. Both commanders had the same idea: attack the other.

Early in the sultry morning of August 10, Lyon made the first move. Splitting his 5,500 men into two columns, he attacked a portion of McCulloch’s 12,000 troops along Wilson’s Creek, a small stream that flowed some 12 miles southwest of Springfield. The surprised Southerners fell back to a new position, where they were joined by reinforcements. Once reorganized, the Confederates launched a series of three counter attacks, failing each time in their effort to breach the Union position. In one of those assaults, General Lyon was killed as he was maneuvering his men into position, giving him the dubious distinction of being the first Union general to be killed in battle. He was replaced by Major Samuel Sturgis. While this was all going on, the second Union column, commanded by Colonel Franz Sigel, was overwhelmed and driven back.

When the Confederates pulled back following their third assault, Sturgis did the same. Short on ammunition, Sturgis ordered his exhausted troops to return to Springfield. McCulloch chose not to pursue his foe.

Union casualties at Wilson’s Creek numbered nearly 1,300 or about 23%. Although McCulloch had twice as many troops, his casualties were slightly less at about 1,200, representing a rate of 10%. It had only been three weeks since their victory at Manassas, and this second victory so early in the war provided the Southerners with a major morale boost and had the effect of giving the Confederacy control of that portion of Missouri.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

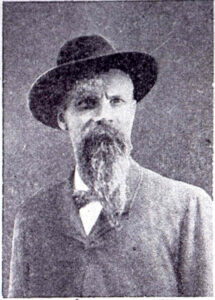

Nicholas Bouquet, born in Landau, Bavaria, was sent to live in the United States by his family when he became eligible to be drafted into the German army. He settled in Burlington, Iowa, and worked at various times as a coppersmith, barrel maker, shopkeeper, policeman and restaurant owner. A few years after arriving in the United States he married Elizabeth Lang, and the couple would have 11 children, two of which died before reaching the age of three.

In April 1861, following the attack on Fort Sumter, he enlisted into the 1st Iowa Infantry, serving in Company D. Now it was early in August, 1861, and the men of the 1st Iowa Infantry were nearing the end of their enlistment. Nobody on either side had expected the rebellion to last much longer than three months, but it was now in its fifth month with no end in sight. The regiment had just been asked if they wanted to be discharged or would they prefer to stay in service until after the expected battle at Wilson’s Creek. Aside from one small skirmish in which only a small portion of the regiment had taken part, the men had not seen any action, and they unanimously agreed to stay on and fight.

On August 10, 1861, they got their wish. Companies D and E were assigned to support Captain James Totten’s Battery at Wilson’s Creek. That position ultimately plunged them into hand to hand fighting in the Confederate counter assaults, each time pushing their assailants back.

In the Rebels’ final attack, one of the horses in Totten’s battery was killed, still harnessed to a gun. Unsure if their foe was going to launch another attack, Major Sturgis ordered a retreat. With no time to remove the dead horse from the team, the gun was in danger of being left behind. If captured, the gun could be turned on the backs of the retreating Federal army. The result would have been disastrous.

Spying a riderless horse rushing between the two lines, seemingly crazed by the pandemonium raging around him, one of Totten’s gunners shouted to Bouquet, asking him if he would help catch the horse and use the animal to move the gun. Bouquet immediately agreed.

Ignoring the bullets from both sides that zipped past them, Bouquet and the gunner pursued the horse, finally succeeding in capturing the panic-stricken creature. They quickly led the animal to the gun and hitched him to it as McCulloch’s men drew closer. Alternating their attention from the harness to the approaching enemy, the two fumbled with the straps until the hitch was complete. As rapidly as they could, they persuaded the team to follow their retreating comrades, and shortly the gun was safely within friendly lines.

On February 16, 1897 Bouquet was awarded the Medal of Honor for his part in saving the gun. His citation read: Voluntarily left the line of battle, and, exposing himself to imminent danger from a heavy fire from the enemy, Bouquet assisted in capturing a riderless horse at large between the lines and hitching him to a disabled gun, saved the gun from capture.

Bouquet passed away on December 27, 1912 and was interred in the Aspen Grove Cemetery in Burlington, Iowa.

If you would like to support the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s mission to preserve the legacy of the Medal of Honor and its Recipients, please consider donating to our foundation here.