William H. Carney: The First Medal of Honor Action by an African-American

For those who have seen the movie ‘Glory,’ the story of the assault on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 is a familiar one. Situated on Morris Island in Charleston…

In 1861, Richmond, Virginia, was no different than most other cities in the United States, in that there were no permanent defenses to protect the city. That would quickly change. As the capitol of the Confederacy, everyone knew Richmond would be a target of the Union army if the rumors of a war came to fruition. Even before the first shot was fired, and believing war was inevitable, engineers began to build those defenses in the form of fortifications ringing the city. One of those forts, Fort Harrison, was at Chaffin’s Farm (historically known as Chapin’s Farm), sitting on a large open bluff above the James River.

In 1864, Union General Ulysses Grant made a move to capture either Richmond or nearby Petersburg with simultaneous assaults north and south of the James River. Under General Benjamin Butler, Union forces launched the northern attack on September 29, 1864. Butler sent part of his army to attack Fort Harrison, while a brigade of US Colored Troops (USCT) was sent to attack the high ground of New Market Heights. Despite heavy casualties, particularly within the ranks of the USCT, both attacks proved successful. However, other assaults bogged down and were unsuccessful at other Virginia defensive installations like Fort Gilmer, Fort Gregg, and Fort Johnson.

The battles, destined to become known as the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, was considered a Union victory and was marked by several heroic efforts by the U.S. Colored Troops from the Tenth and Eighteenth Corps. Of the 25 Medals of Honor earned by African-Americans during the Civil War, 14 were awarded for actions at Chaffin’s Farm.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

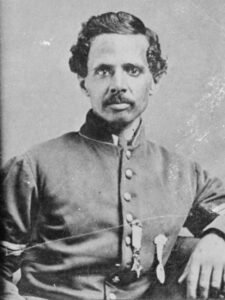

Powhatan Beaty was born in Richmond in 1838. Although his parents were free, children were not automatically granted their freedom in the old South, and Beaty was considered a slave. It wasn’t until Powhatan’s parents took him to Cincinnati, Ohio, when he was 12 years old that he gained his freedom. In Cincinnati he attended public school, fell in love with acting, and became an apprentice furniture maker after graduation.

On June 7, 1863, Beaty enlisted in the Union army at age 24. Two days later he was promoted to sergeant, and at some point he married Mary C. Seddon. The two would have five children, with only two surviving into adulthood.

At the time of his enlistment, Beaty expected to be placed in either the 54th Massachusetts or 55th Massachusetts, the only two Black regiments at the time. However, those regiments were already at full strength, so Ohio Governor David Tod requested and received permission to form a Black regiment from Ohio, which would become the 127th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. In turn, the 127th Ohio became the 5th United States Colored Troops.

The 5th USCT saw a significant amount of action, fighting at Sandy Swamp, the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, the capture of City Point, and the Battle of the Crater at Petersburg. On September 29, 1864, the 5th USCT was at Chaffin’s Farm and New Market Heights, with Beaty serving as 1st sergeant of Company G.

When Company G was ordered to move on the center of the Confederate line on New Market Heights, the fear level among the men of the company rose exponentially. Those who realized what was ahead of them recognized the order as a suicide mission. The Confederates were firmly entrenched and there would be little cover on the steep uphill assault.

As expected, the fighting was intense and bloody. In the assault Beaty’s knapsack was shot off, as was his cap. Another bulled tore the sole off one of his shoes. Yet another bullet passed through his canteen, draining it. Company G was forced back, with the color bearer being killed in the retreat.

When Beaty learned that the colors were still out on the field, he made a one-man dash of some 200 yards (some sources say 600 yards) through heavy enemy fire to retrieve the banner. Somehow, he did just that, then returned to G Company’s new position unscathed. When a head count was taken, Company G had lost all of its officers.

Beaty, now more angry than scared, gathered what remained of Company G and led a second assault on the Rebels, this time forcing the Southerners to abandon their position. When the fighting was over, Company G only had 16 of its original 83 men still standing, the rest being killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

Witnessing what Beaty had done, General Butler commended him for his bravery and leadership. His commanding officer recommended him for promotion on two separate occasions. Neither one was acted on. The army was not yet ready to promote African-Americans to an officer’s position, although Beaty did receive a brevet promotion to lieutenant.

Six months later, on April 6, 1865, Beaty finally received a more tangible recognition – the Medal of Honor. His citation read: Took command of his company, all the officers being killed or wounded, and gallantly led it. He had been nominated for the honor by none other than General Butler.

At war’s end Beaty, by then a veteran of 13 battles and many more skirmishes, mustered out and returned home to Cincinnati, where he worked as a janitor and resumed his love of acting. Forming his own Shakespearean company, he became one of the few African-American actors to achieve a measure of success, receiving glowing reviews in places such as Philadelphia, Washington, and Indianapolis and becoming an honored guest at a dinner given for noted abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Powhatan Beaty passed away December 6, 1916 and was buried in Union Baptist Church Cemetery in his adopted hometown of Cincinnati.

In 2000 the United States Congress honored Beaty once again, naming the Interstate 895 bridge over Virginia Route 5 the Powhatan Beaty Memorial Bridge.

Additional Reading: