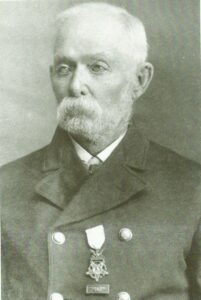

Capture the Flag: Corporal George W. Reed

During the U.S. Civil War, many Medals of Honor were awarded for capturing the enemy's flag. George W. Reed was the recipient of one such award on September 6, 1864,…

The Civil War was nearing its end, and now-confident Union generals saw their opportunity to deal a death blow to Southern forces in the deep south. On April 8, 1865, Union forces under Major General Edward R. S. Canby captured Spanish Fort, near Mobile, Alabama. Canby’s 16,000 troops, including some 5,000 African-Americans, moved on Fort Blakely the next day. Confederate General St. John R. Liddell’s 3,500 defenders were unable to repel such a large force, and after a relatively short fight, Liddell’s men were forced to surrender. The Confederacy breathed its last along with the fort, and that same day Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Union General U. S. Grant, ending the war.

By James Gindlesperger, historical author

The fighting was fierce along the two-mile line of Confederate works on April 9, 1865. Despite the determined resistance being thrown up by the southern fighters inside Fort Blakely, however, there was little doubt as to what the outcome would be. Union forces outnumbered the defenders by more than 4:1. It would only be a matter of time.

Captain Samuel McConnell of the 119th Illinois Infantry’s Company H had just received orders to take Company H to the front of the line and lead the regiment in an assault on the fort. Ignoring the Alabama heat that caused perspiration to run down his forehead into his eyes, he lined the company up into double rank, with the first rank about six paces ahead of the second. The rest of the regiment formed a line of battle about 50 paces behind the second rank.

The assault proved to be deadly for the regiment. McConnell would later report that the Southerners fired into his ranks with lethal precision, every volley removing more men from the line. McConnell would emerge unscathed, although his clothing showed several bullet holes after the battle.

Reaching the fort’s breastworks, McConnell stopped to catch his breath. Looking around, he spied Private John Wagner. Most of the other men from Company H had already been killed or wounded so badly that they couldn’t advance. The few that were still in the fight had scattered, barely visible now through the smoke.

Three large Confederate guns stood just ahead, positioned on such an angle that their field of fire was cutting swaths into the rest of the 119th Illinois following Company H.

Hoping the gunners wouldn’t see him through the smoke, McConnell motioned to Wagner that he was going to try to scale the breastworks. Wagner nodded that he understood, and when McConnell stepped off, Wagner followed. Just as they reached the guns, all three fired another deadly volley. The two men from Illinois were not hit by the discharge, but both had gotten so close to the guns that they were knocked over by the pressure from the blast. Tumbling backward into a ditch, both scrambled to their feet and scaled the works before the guns could be reloaded. The surprised gunners immediately scattered.

Now inside the works, McConnell and Wagner moved to their left, where the fort appeared to have fewer defenders. With the smoke concealing their movements, they found themselves coming into the rear of a color-guard, including their color bearer. The Confederates spied the two at almost the same time, and several fired on them from a distance of about 30 paces. Fortunately for McConnell and Wagner, none of the shots found their targets. McConnell fired back at the color bearer, striking him and causing him to drop his flag.

Not realizing that McConnell and Wagner were unsupported, and having no idea that McConnell had just fired the last round from his pistol, the remainder of the Rebels fled. McConnell rushed toward the color bearer’s prone body and seized the fallen colors. Not long after, the fort was surrendered.

Three months later, on July 12, 1865, the regiment gathered for Parade with the rest of the 16th Corps at Brigadier General William Sooy Smith’s headquarters in Mobile, Alabama. There, McConnell and Sergeant George F. Rebmann of the regiment’s Company B, who had also captured a flag at Fort Blakely, were presented with the Medal of Honor by Lieutenant J. L. Lyon, Assistant Inspector-General for the Corps.

McConnel’s citation read, “While leading his company in an assault, Capt. McConnell braved an intense fire that mowed down his unit. Upon reaching the breastworks, he found that he had only one member of his company with him, Pvt. Wagner. He was so close to an enemy gun that the blast knocked him down a ditch. Getting up, he entered the gun pit, the gun crew fleeing before him. About 30 paces away he saw a Confederate flag bearer and guard which he captured with the last shot in his pistol.”

McConnell would say years later that the memory of receiving the Medal still gave him enjoyment of the “. . . pleasant sensations of that day.”

McConnell died on March 26, 1915 in Havelock, Nebraska, and was buried a few days later in Arborville Rural Cemetery in Bradshaw, Nebraska.